Recommended Links

- Sign up for free newsletter to get regular emails about competitions: Winning Writers

- Sign up for free newsletter to get regular emails about competitions and story markets: Freedom With Writing

- This link is specifically for markets that accept submissions by teens: Magazines that Publish Children & Teens

- Kid/teen-only opportunities: BAZOOF! Magazine (nonpaying?) and StoryStudio Contests

- Tracking services: The Submission Grinder, Submittable, Duotrope or just in Excel. (These sites can usually be used to search for opportunities as well.)

Identify Your Goals

This might seem obvious (and it applies to all of publishing, not just short fiction), but it’s actually very important to really dig into what matters to you.

Are you building a long-term career? Do you dream of publishing full time? Do you care more about money or creative freedom or acclaim? Is it really more about getting your stories or ideas out to the world? Do you crave feedback? Is writing really a private pursuit that brings joy to you but that you don’t want the eyes (and opinions) of the world on? Is publishing a path to something else—recognition, acclaim, support for a different eductational or career trajectory?

Your answers may surprise you and/or change over time—which is fine! We all do the best we can and move forward as best we can, making mistakes along the way. But if you can clarify your goals (and dreams and hopes and . . . ) it’ll help you think critically about the information available and choose the most promising path for your needs.

Ways To Connect With Readers

This is vital: if you want to get your work out into the world, that means working with others.

Young writers and newcomers may be used to a more critical perspective on “literature” (damage from high school/college lit classes, no doubt), or channel their insecurities into aggression, or simply lack the experience to recognize just what (and to what extent) they don’t yet know.

Time for a change of focus: other writers are now your peers. Not long-dead entities to be picked apart in analysis and critique. Not competitors (even when they are). Not faceless corporations. Real people who you may bump into from time to time, friends, colleagues, possibly even someone who will one day be in a position to help or hurt your career. Proceed accordingly.

Try to adjust your perspective on other emerging writers and readers as well; they’re now potential friends, colleagues, and fans. Be kind. Be helpful. Be professional. Don’t be scared.

You’ll need people who are on your side (or at least willing to lend a hand temporarily) at nearly every step of your writing journey. People who’ll share tips, give feedback (if you ask for it), buy books, write reviews, shout about your books to other readers.

If you intend to publish a book or otherwise care about getting your words out to readers, it’s never too early to start. Nothing published to share yet? Build platforms (website/social media, etc.) around shouting about books you like, ideally ones that are similar to what you hope to write. By the time you’re ready to search for readers, you’ll have contacts who you can share the news with!

And consider starting with something smaller and less resource intensive than a book, especially if you’re a student. Short stories, fanfiction, and serial fiction are a few ways to get your words in front of readers with less pressure. Bite-sized content is a growing market and it’s more doable for you, especially if you’re balancing creating with a busy school or work schedule.

At time of writing, Wattpad and Archive Of Our Own (AO3) are the biggest fanfiction platforms. Use filters to keep content kid-friendly if you’re underage or simply uninterested in the thriving adult content sections. ;)

Quick aside: ALWAYS read the contracts before sharing your work and make sure your rights are protected. More on that in a bit.

Establishing Your Reputation/Skill

This section was originally intended for students, but writers of all ages can get into sharing their words for reputational purposes.

Students may find it helpful in scholarship, college, or job applications. Adults may simply want the prestige, or use it as a (small) building block to a writing career or a complement to a different field.

Awards and accolades don’t sell lots of books. They can be useful in building a “brand” as a writer, however, and may lead to more opportunities or visibility over time.

Larger scale or higher profile awards or story markets can be more beneficial, but the competition will be higher. That’s not to say don’t enter—always take your shot! But local/regional and student-specific competitions/markets will be relatively easier to make a splash in. Also note that certain topics or styles will play better with some judging panels or editors/magazines than others. The closer you match their preferences, the more likely you are to get a ‘yes’ and that has nothing to do with skill or quality. (Don’t get discouraged!)

While publishing as a teen may sound promising, it tends to be less of a selling point than you might think. Unless you’re entering a student competition or otherwise required to disclose such details, avoid mentioning your age/grade.

Earning an Income With Short Fiction

Writing is not known for it’s incredible financial rewards—usually. That doesn’t mean it won’t or can’t pay, but the effort tends not to pay off quickly or reliably. Don’t overreach. The next section dives into rates, but in terms of markets, you can place short stories in competitions, print and/or genre or literary magazines or ‘zines, other types of magazines that sometimes include a small fiction segment, anthologies, or individually be self-publishing.

Reading submission guidelines and writing a custom piece in response sometimes results in better (=closer) fits, but you can also just write freely and then look for the right market after the fact. Note that preparing, submitting, and tracking story submissions takes time in its own right, putting further pressure on any income you might recieve.

Nonfiction (particularly business) writing tends to be paid at higher rates, but you normally pitch the idea of a feature or article to an editor before writing, whereas with fiction, you write the whole piece and submit it.

Short Fiction Rates

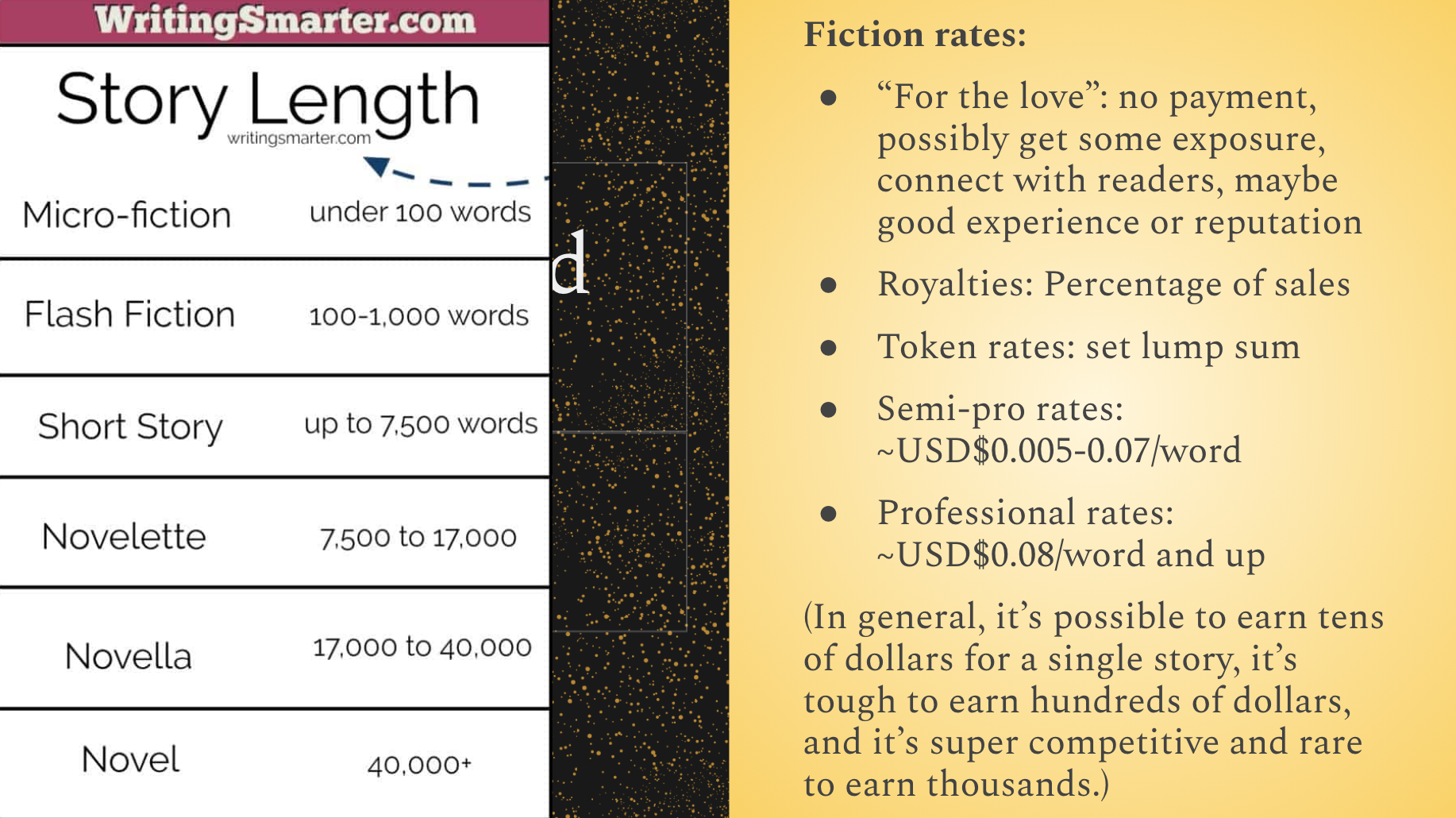

Graphic from writingsmarter.com.

Always ALWAYS read the submission guidelines. There is variation between accepted story lengths and rates of pay. But this works fairly well as a general guideline. Note that professional writers tend to speak in terms of wordcount because page count varies depending on formatting and is an unreliable indicator. We really only use it to speak to readers who are used to thinking in those terms.

Many short fiction “markets” do not pay. Some are prestigious; many are new and/or hobby projects for the founder. That doesn’t mean they’re automatically bad! They make be a good stepping stone or practice for beginners, or provide an outlet for those who love sharing their words but aren’t bothered about the income side of things. As usual, always read the terms/contracts/guidelines to make sure you’re not signing away more rights than you mean to.

We’ll look at rights/licensing in a bit, but it’s good to keep in mind that the first sale is usually the most valuable and accessible to make, and consider holding out for a “higher” level market. Reprints aren’t as widely accepted in paying markets, and it’s harder work to place them. In general, I recommend shooting high and then working your way down a wishlist of possible story markets until a story lands.

Magazines and other short fiction markets rarely pay on royalties, but the exception is anthologies. Sometimes they’re paid in a lump sum upon signing, but “royalty-split” arrangements aren’t uncommon. While your income is therefore unreliable, this can be a good option if you’ve built a platform of readers eager to pay for your work and/or the other authors in the anthology have a strong platform to market to as well.

Token rates are generally in the $5-$40 range, where the market can’t afford more but feels it’s important to pay something. The Science Fiction Fantasy Writers of America (sfwa.org) has set pro rates at $0.08/word, but you’ll see anything from half a cent on up. Some markets also offer lump sum payments in the 100+ range. Generally, the more they pay, the more the competition, but don’t self-reject—the worst they can do is say no!

Gut Check Break!

I’ll keep repeating this, but ALWAYS read the submission guidelines and follow them. Your story should be creative; your formatting and document presentation should not be. If no specifics are given, follow Shunn Manuscript Format, modern edition as the default.

Some competitions charge entrance fees. Some writing markets charge reading fees, but far from all. You can spend a lot of money trying to get published, but you don’t have to. Avoid fee-charging markets or competitions unless you think your story has an excellent chance of earning the expense back or unless money is no object.

It’s easy to get caught up in the pursuit. After a few submissions, you just really really want an acceptance. Try to clarify your goals and keep them front and center. Write them down and post them in your workspace if that helps.

On a related note, always read the contract. Some market post a sample one. Most competitions will also post terms. Some “opportunities” aren’t. See other posts in the Resources section for links to reading, understanding and negotiating contracts.

Consider the reader(s) before submitting. What kind of reader is likely to appreciate your story (if it’s already written). What might the judges or first readers/editor care about and appreciate? You can research past award-winners or other stories in a magazine to get an idea, but if you’re submitting a lot, it’s not practical to do too much research.

Finally, make yourself a tracking document or spreadsheet early on. Keep track of submissions, contract terms for licensed stories, and details of the stories themselves. This seems silly at first, but if you keep writing and submitting, you’ll quickly get beyond the point where you can keep track in your head.