Recommended Resources

Young writers and emerging authors often ask me how to get started or do x or y in workshops and panels. Here's a collection of resources I've found helpful and recommend!

Most slides are from a series of workshops for young writers and present a rough and very broad overview of things to think about and possible next steps for emerging authors.

I've also filmed a couple mini writing tips on social: Spooky Middle Grade & Speculative Worldbuilding

Disclaimers: your mileage may vary, never accept 100% of what you’re told, do your own research, etc. The important thing here is to think critically and choose the right path for YOU and your work.

Essential reading: these blog archives and weekly business-for-writers blog by Kristine Kathryn Rusch are gold.

- The blog archives and weekly business-for-writers blog by Kristine Kathryn Rusch is gold. This section is particularly essential: Contracts & Dealbreakers

- The Plot Whisperer: Secrets of Story Structure Any Writer Can Master by Martha Alderson (gets a little new-age-y but generally provides a good foundation)

- Developmental Editor Lisa Poisso collects useful resources on her Clarity subsite

- Reedsy offers plenty of free articles, guides and mini courses on their blog

- The Creative Penn offers a wide variety of learning resources (delivered authoritatively, but take with a grain of salt) on this blog

- Sign up for free newsletter to get regular emails about competitions: Winning Writers

- Sign up for free newsletter to get regular emails about competitions and story markets: Freedom With Writing

- This link is specifically for markets that accept submissions by teens: Magazines that Publish Children & Teens

- Kid/teen-only opportunities: BAZOOF! Magazine (nonpaying?) and StoryStudio Contests

- Tracking services: The Submission Grinder, Submittable, Duotrope or just in Excel. (These sites can usually be used to search for opportunities as well.)

- The blog archives and weekly business-for-writers blog by Kristine Kathryn Rusch is gold: Contracts & Dealbreakers

- Reedsy offers plenty of free articles, guides and mini courses on their blog

- CreativIndie has tons of well-developed resources on this site

- David Gaughran is well known as an indie publishing guru, sharing books, articles, newsletters and courses on his site

- The blog archives and weekly business-for-writers blog by Kristine Kathryn Rusch is gold. This section is particularly essential: Contracts & Dealbreakers

Publishing Overview

11 Jul 2021

Recommended Resources

Disclaimer: many free resources are provided in hopes that you’ll invest in a product (workshop, book, mentorship program, etc.) Don’t invest in anything until you understand it well enough to know if you’re getting a good deal.

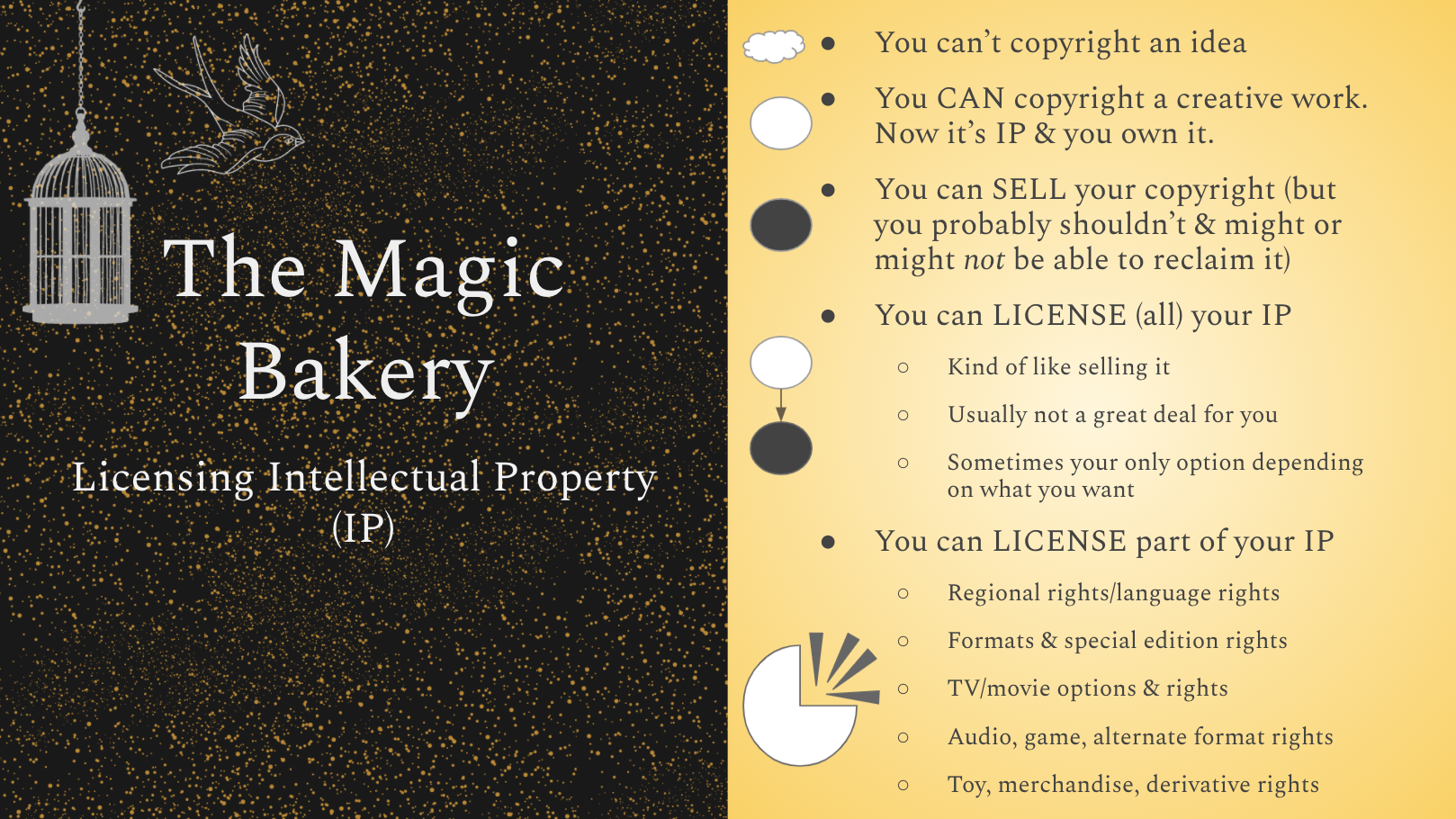

Licensing & YOU

Experienced and prolific author/editor/publisher Dean Wesley Smith talks about the idea of a “magic bakery’ when it comes to writing. You can read about it in his own words and in this excellent blog by his wife, Kristine Kathryn Rusch. But, in a nutshell, the concept is that intellectual property—like our writing—can be sold over and over, in part and in whole, unlike other goods.

Your work automatically belongs to you from the time of its creation. You own full copyright. (The exception is when you’re writing as work-for-hire, or working on an IP project that belongs to someone else, like a Star Wars tie-in novel, for example.) Technically, you could transfer copyright in a sale (if you sign a terrible contract), but don’t.

Instead, you license the right to use the work in part or in whole. Some examples: Licensing first publication rights in English, then, when the exclusivity period expires, licensing reprint rights (over and over again) or publishing it yourself as a standalone or in a collection. You can also license (and re-license) translation rights, audio rights, production rights (for film/tv), merchandising rights, etc. All that off of one story (potentially).

The moral of the story? Keep your copyright, don’t license more rights than the licensee will use (to your benefit), and make sure your contracts aren’t perpetual (so you can get licensed rights back eventually and re-license them.)

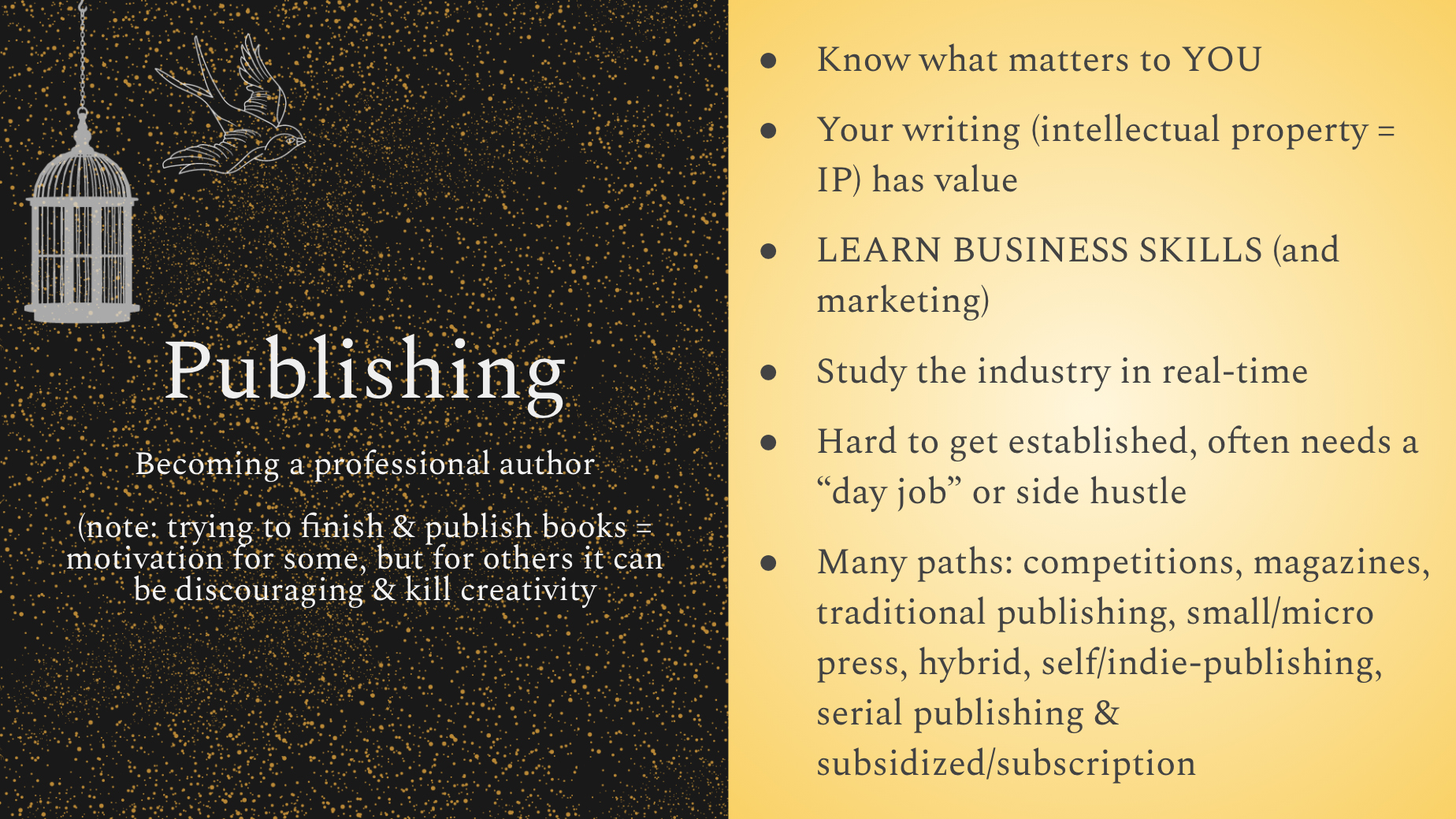

Publishing Novels

They’re a bigger effort in terms of time, skill, and investment, but novels are not inherently better than any other type of fiction. Try not to feel pressured into writing one if you don’t really want to!

Whatever publishing path you choose, you will become a small business. Like any entrepreneur, you’ll need to learn business skills and keep up on your industry, even if it’s just a side hustle. Do your research as you approach publishing; things change in a matter of months in this industry, much less years, and you don’t want to be launching with outdated intel. See other posts in the Resources section for links to groups and news outlets for staying up to date.

Publishing can pay, but it’s usually a slow and gradual path to earning an income. Royalties can accumulate over time. The opportunity to sell additional licenses may emerge. The more stories/books you have out, the more it all can add up, but that takes time, too. Make a plan for how you’ll survive financially for the first years at least.

Be open to nontraditional routes: serial fiction and subsidized or serialed fiction are looking strong right now. Patreon and Kickstarter are good examples of emerging trends that authors have leveraged to the advantage of their careers.

One Route

Not much to add here. This is roughly what I do these days. It’s pretty minimal compared to some, unneccessarily complex compared to others. I can’t quite bring myself to draft-proofread-publish, but I’m not doing multiple rounds of heavy rewrites, either. If I get really stuck on the plotting, I’ll change formats, which can look like any of these:

|

|

|

|

|

Story Mapping

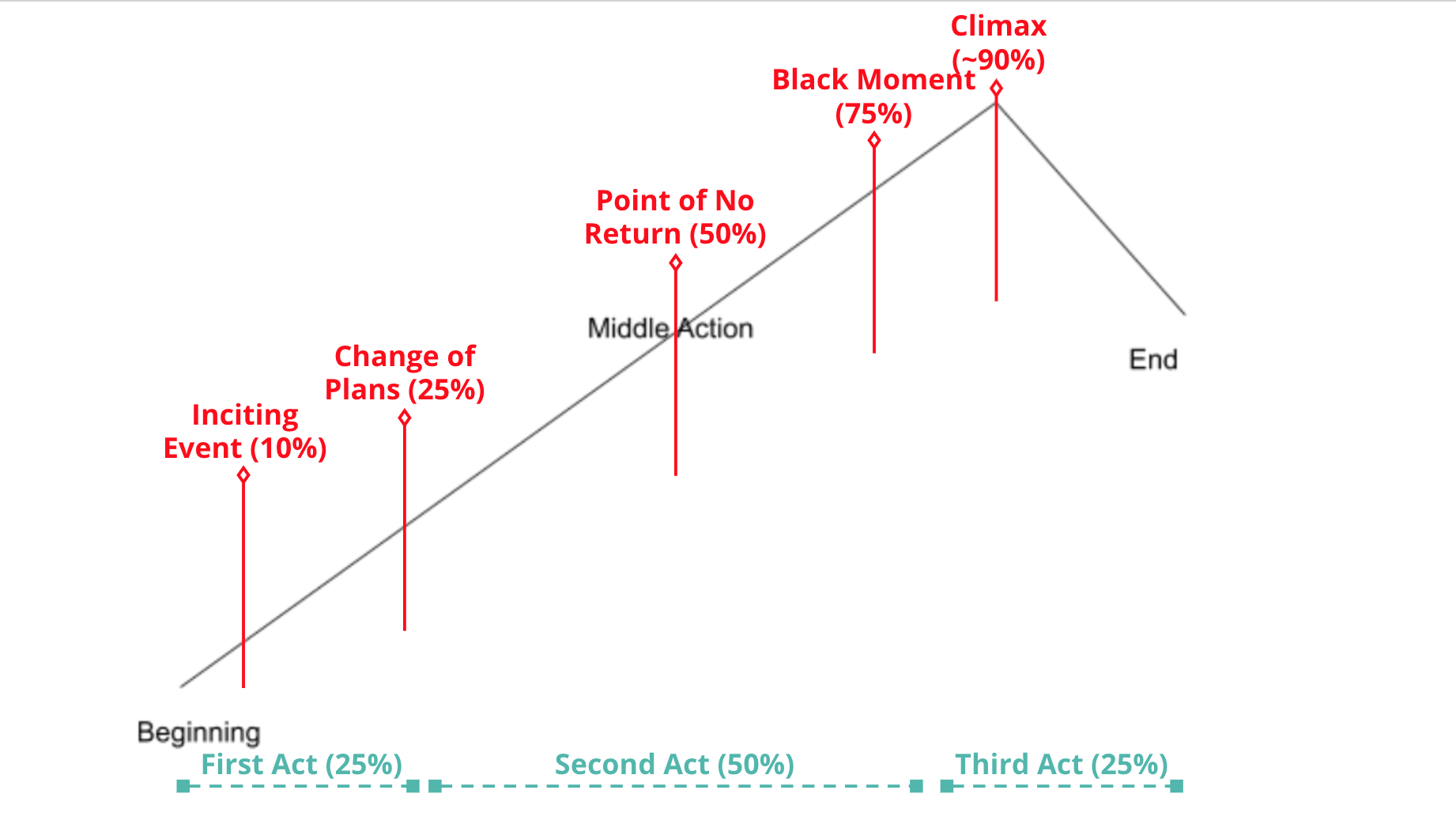

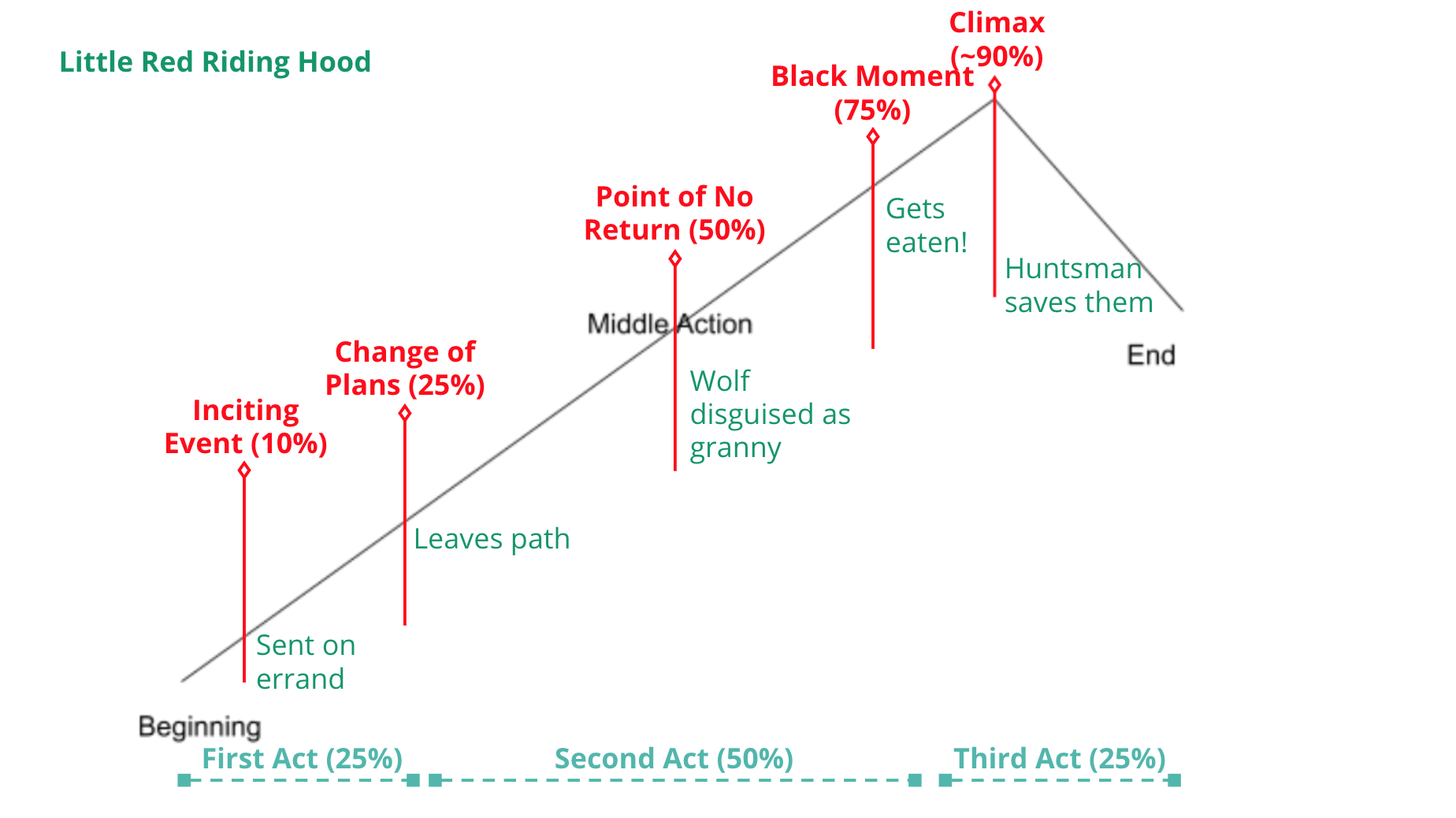

While all the charts and cards can look complex, the basic structure I’m using is a three act structure with four quarters.

The first quarter and the first act map together and contain the inciting event early on (at about the 10% mark). Something disrupts the main character’s ordinary life and sends them in a new direction. It ends around the 25% mark with the change of plans turning point. This is where the main character chooses (or gets dragged into) the adventure/quest/journey of the story.

The second act is easiest to understand if you split it evenly in two. The first half is the character struggling to make forward progress and understand their situation/world/challenge/self etc. Around the 50% mark or midpoint turning point (end of the second quarter) they make a discovery or realization that shifts their trajectory.

Now, starting the third quarter, the main character(s) (thinks they) know what they need to do to succeed, though they still face obstacles. The second act/third quarter ends with the black moment turning point, the darkest point of the story, either figuratively or literally involving death. The main character may feel as though they’ve failed, there’s no hope, maybe no point going on. They may be focused on revenge or retribution.

But, into the final quarter/act, they’ll need to rally enough to take on the greatest challenge of the story in the final turning point, the climax. Often this follows a mini arc of setting out, making progress, making a sudden realization that changes their perspective or goal, hitting a “black moment” of despair, and then rallying to overcome (in a positive story arc, at least). There’s often an inner and outer component to this, the main character finding inner strength or understanding in order to overcome the outer challenge of the story. The last 10% or so of the final act wraps up the story by showing the new normal—and/or setting up a sequel.

Little Red Riding Hood isn’t the best example because it’s missing main character agency in most variations. Ideally, you want your main character’s actions and choices to be integral to every turning point.

If you hate how structured this all is, welcome to the club. I fought this idea hard—but it really does result in faster drafting and stories readers seem to enjoy more. And there’s tons of room for creativity within this loose structure. Also, those percentages will come in handy in a moment.

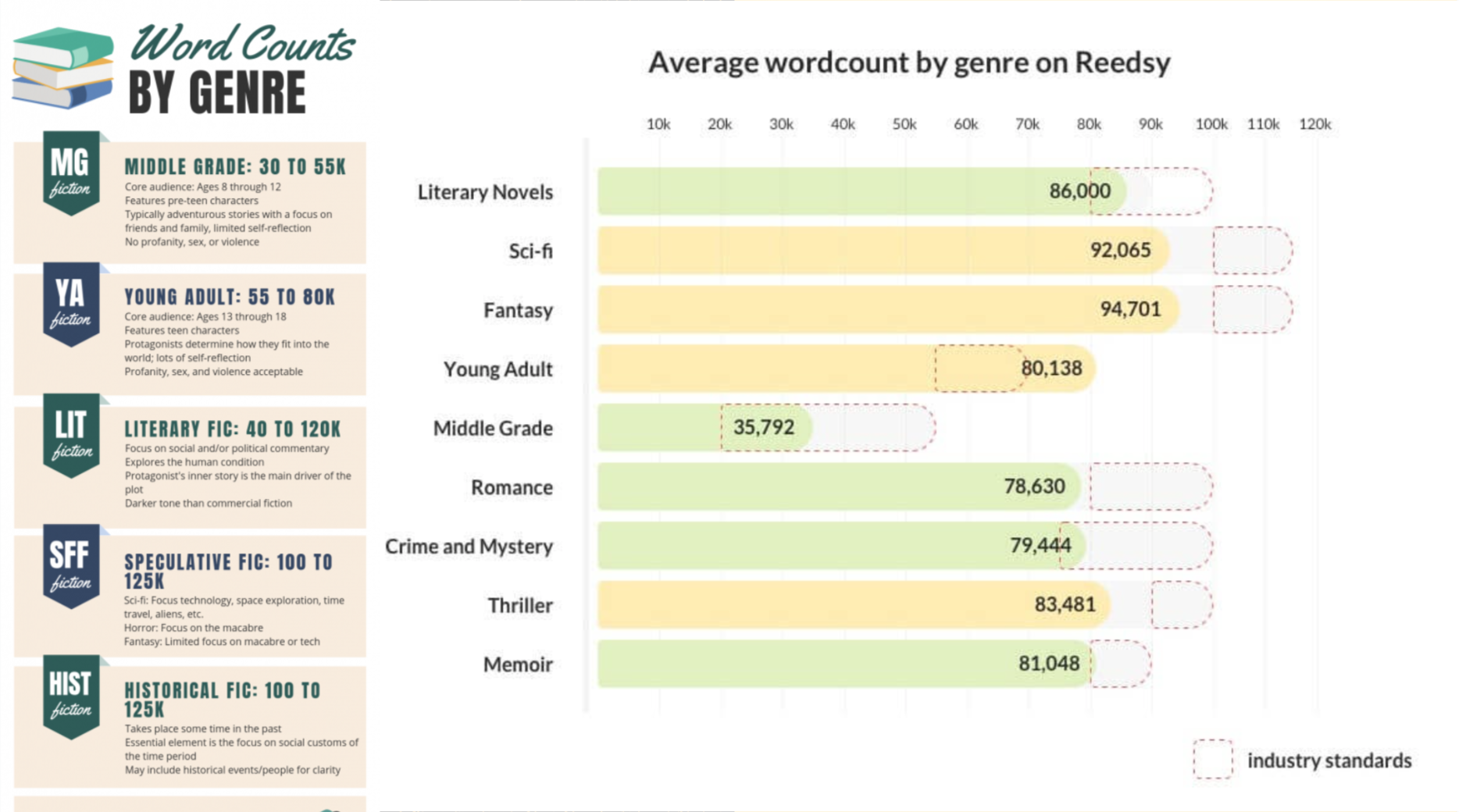

Word count graphics from btleditorial.com & Reedsy.

Word count graphics from btleditorial.com & Reedsy.

|

|

Math For Authors

Everyone’s favourite, right? But hang in there, this comes in really handy.

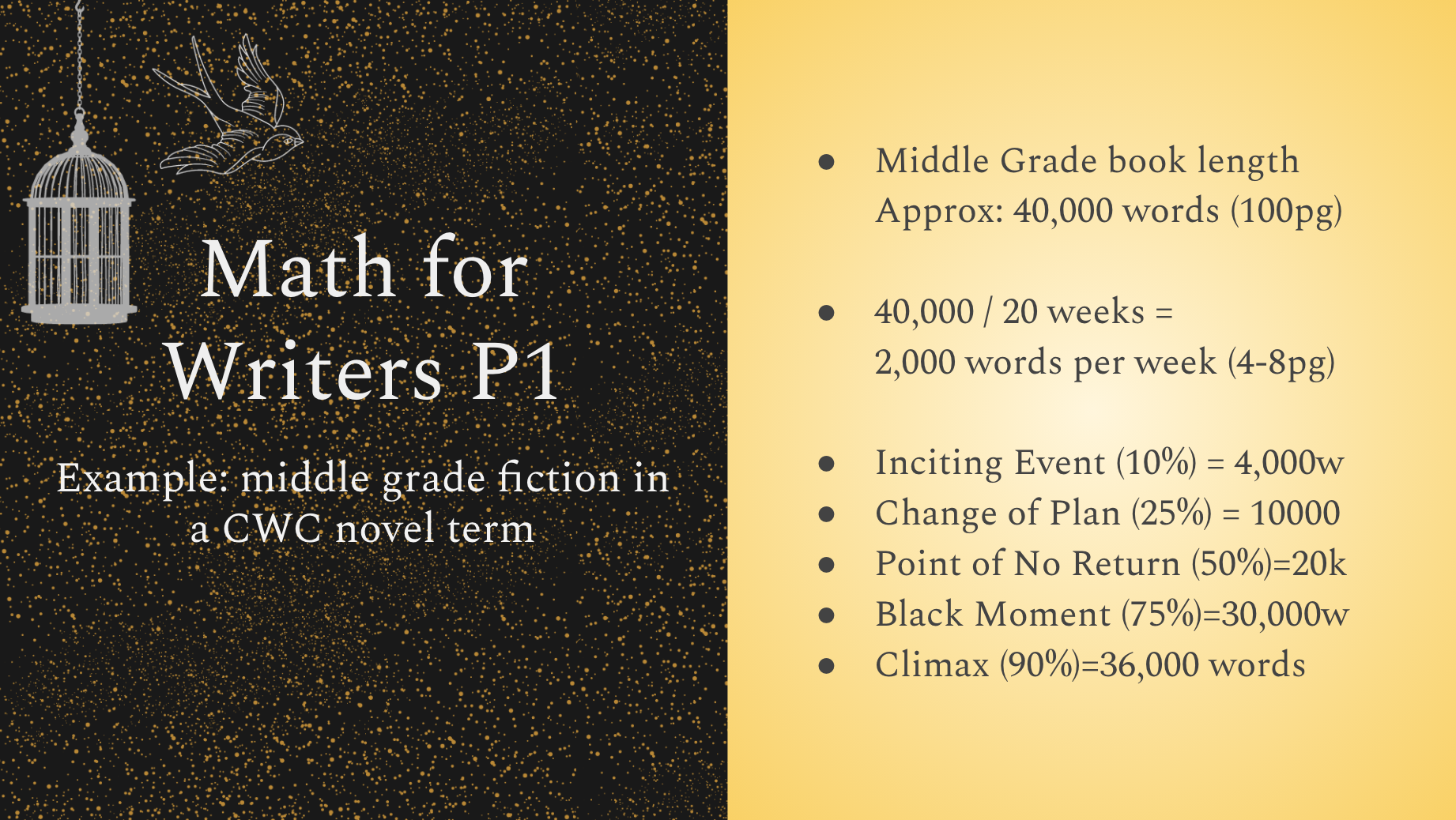

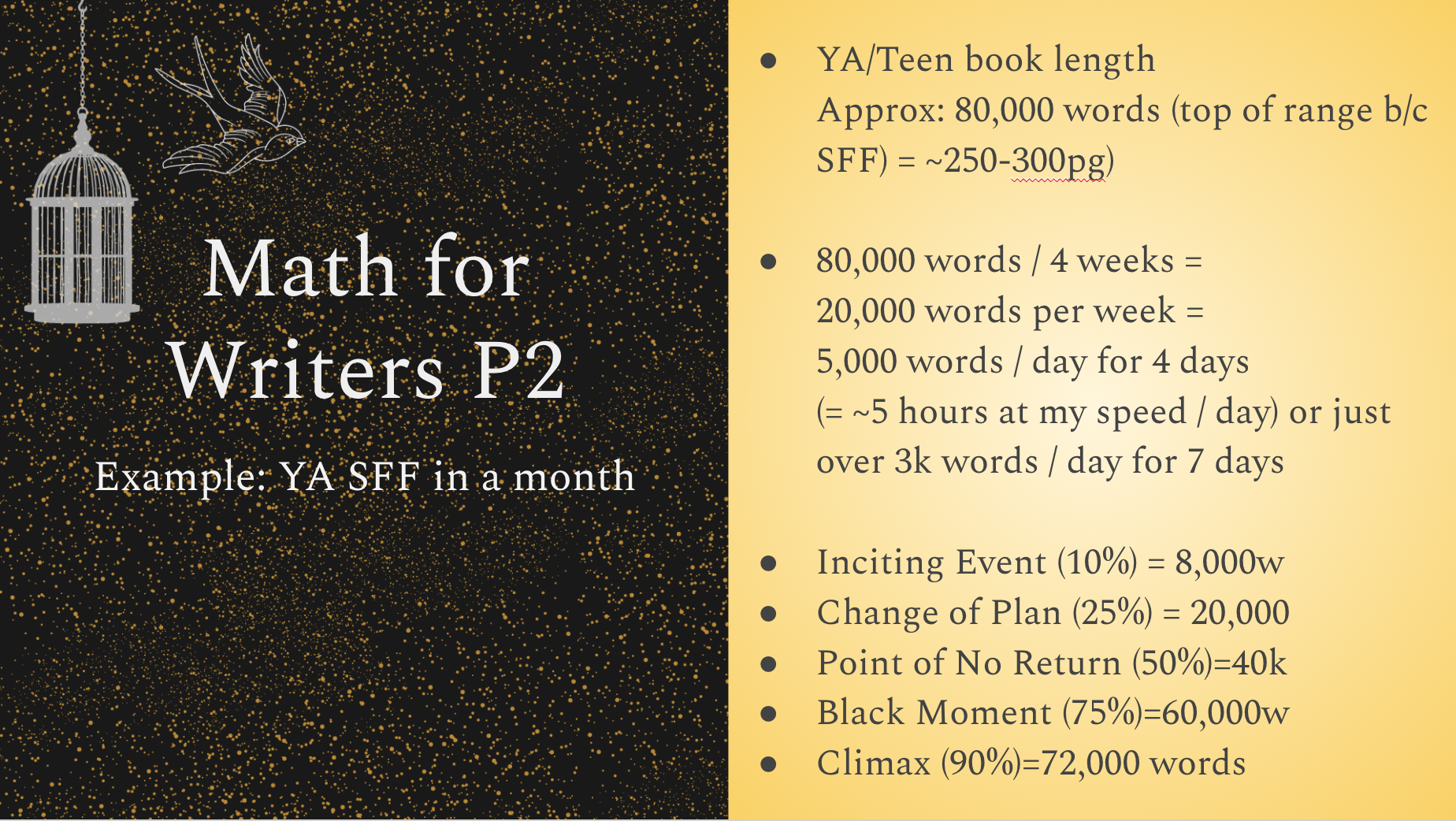

You can apply the turning point percentages we just looked at to a target wordcount (above) to plan how to draft your novel. Pick a target wordcount, jot down some notes about each turning point (or go in blind, if that’s your preference), and track your wordcount as you write.

For instance, if you’re planning an industry-standard middle grade novel (40,000 words, say), as you’re coming up to 15,000 words you know you’ve got the midpoint coming up and you need to get your character in place within the next 5,000 words or 4-5 hours of writing.

If your target is 80k words for a YA fantasy, you’re going to be preparing to write that midpoint as you near 40k words (or try to include an inciting event within the first 8k words, or a black moment around the 60k mark, etc.) These intervals help make stories feel like they’re moving along at a natural clip to western readers who are mostly used to this story pattern. If you’re far off these proportions, it can manifest as portions of the story feeling slow-paced or rushed.

But, as with all writing advice, you can take it or leave it. Other story structures exist. Some writers have stronger instinctual structure, while others find it easier to write to a plan. There’s no one right way, but if you’re not sure where to start, I suggest trying this structure.

Short Fiction Overview

10 Jul 2021

Recommended Links

Identify Your Goals

This might seem obvious (and it applies to all of publishing, not just short fiction), but it’s actually very important to really dig into what matters to you.

Are you building a long-term career? Do you dream of publishing full time? Do you care more about money or creative freedom or acclaim? Is it really more about getting your stories or ideas out to the world? Do you crave feedback? Is writing really a private pursuit that brings joy to you but that you don’t want the eyes (and opinions) of the world on? Is publishing a path to something else—recognition, acclaim, support for a different eductational or career trajectory?

Your answers may surprise you and/or change over time—which is fine! We all do the best we can and move forward as best we can, making mistakes along the way. But if you can clarify your goals (and dreams and hopes and . . . ) it’ll help you think critically about the information available and choose the most promising path for your needs.

Ways To Connect With Readers

This is vital: if you want to get your work out into the world, that means working with others.

Young writers and newcomers may be used to a more critical perspective on “literature” (damage from high school/college lit classes, no doubt), or channel their insecurities into aggression, or simply lack the experience to recognize just what (and to what extent) they don’t yet know.

Time for a change of focus: other writers are now your peers. Not long-dead entities to be picked apart in analysis and critique. Not competitors (even when they are). Not faceless corporations. Real people who you may bump into from time to time, friends, colleagues, possibly even someone who will one day be in a position to help or hurt your career. Proceed accordingly.

Try to adjust your perspective on other emerging writers and readers as well; they’re now potential friends, colleagues, and fans. Be kind. Be helpful. Be professional. Don’t be scared.

You’ll need people who are on your side (or at least willing to lend a hand temporarily) at nearly every step of your writing journey. People who’ll share tips, give feedback (if you ask for it), buy books, write reviews, shout about your books to other readers.

If you intend to publish a book or otherwise care about getting your words out to readers, it’s never too early to start. Nothing published to share yet? Build platforms (website/social media, etc.) around shouting about books you like, ideally ones that are similar to what you hope to write. By the time you’re ready to search for readers, you’ll have contacts who you can share the news with!

And consider starting with something smaller and less resource intensive than a book, especially if you’re a student. Short stories, fanfiction, and serial fiction are a few ways to get your words in front of readers with less pressure. Bite-sized content is a growing market and it’s more doable for you, especially if you’re balancing creating with a busy school or work schedule.

At time of writing, Wattpad and Archive Of Our Own (AO3) are the biggest fanfiction platforms. Use filters to keep content kid-friendly if you’re underage or simply uninterested in the thriving adult content sections. ;)

Quick aside: ALWAYS read the contracts before sharing your work and make sure your rights are protected. More on that in a bit.

Establishing Your Reputation/Skill

This section was originally intended for students, but writers of all ages can get into sharing their words for reputational purposes.

Students may find it helpful in scholarship, college, or job applications. Adults may simply want the prestige, or use it as a (small) building block to a writing career or a complement to a different field.

Awards and accolades don’t sell lots of books. They can be useful in building a “brand” as a writer, however, and may lead to more opportunities or visibility over time.

Larger scale or higher profile awards or story markets can be more beneficial, but the competition will be higher. That’s not to say don’t enter—always take your shot! But local/regional and student-specific competitions/markets will be relatively easier to make a splash in. Also note that certain topics or styles will play better with some judging panels or editors/magazines than others. The closer you match their preferences, the more likely you are to get a ‘yes’ and that has nothing to do with skill or quality. (Don’t get discouraged!)

While publishing as a teen may sound promising, it tends to be less of a selling point than you might think. Unless you’re entering a student competition or otherwise required to disclose such details, avoid mentioning your age/grade.

Earning an Income With Short Fiction

Writing is not known for it’s incredible financial rewards—usually. That doesn’t mean it won’t or can’t pay, but the effort tends not to pay off quickly or reliably. Don’t overreach. The next section dives into rates, but in terms of markets, you can place short stories in competitions, print and/or genre or literary magazines or ‘zines, other types of magazines that sometimes include a small fiction segment, anthologies, or individually be self-publishing.

Reading submission guidelines and writing a custom piece in response sometimes results in better (=closer) fits, but you can also just write freely and then look for the right market after the fact. Note that preparing, submitting, and tracking story submissions takes time in its own right, putting further pressure on any income you might recieve.

Nonfiction (particularly business) writing tends to be paid at higher rates, but you normally pitch the idea of a feature or article to an editor before writing, whereas with fiction, you write the whole piece and submit it.

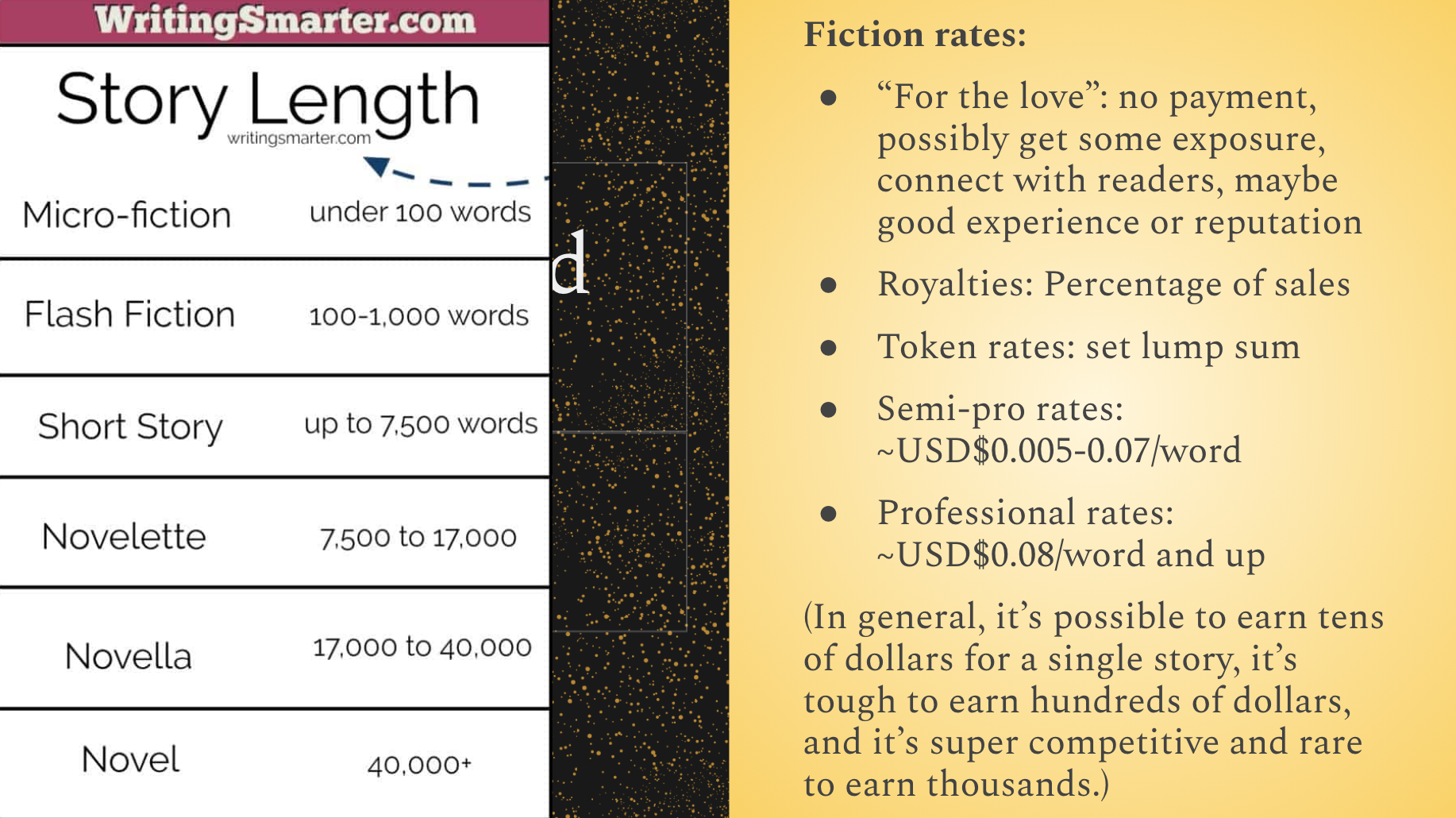

Short Fiction Rates

Graphic from writingsmarter.com.

Always ALWAYS read the submission guidelines. There is variation between accepted story lengths and rates of pay. But this works fairly well as a general guideline. Note that professional writers tend to speak in terms of wordcount because page count varies depending on formatting and is an unreliable indicator. We really only use it to speak to readers who are used to thinking in those terms.

Many short fiction “markets” do not pay. Some are prestigious; many are new and/or hobby projects for the founder. That doesn’t mean they’re automatically bad! They make be a good stepping stone or practice for beginners, or provide an outlet for those who love sharing their words but aren’t bothered about the income side of things. As usual, always read the terms/contracts/guidelines to make sure you’re not signing away more rights than you mean to.

We’ll look at rights/licensing in a bit, but it’s good to keep in mind that the first sale is usually the most valuable and accessible to make, and consider holding out for a “higher” level market. Reprints aren’t as widely accepted in paying markets, and it’s harder work to place them. In general, I recommend shooting high and then working your way down a wishlist of possible story markets until a story lands.

Magazines and other short fiction markets rarely pay on royalties, but the exception is anthologies. Sometimes they’re paid in a lump sum upon signing, but “royalty-split” arrangements aren’t uncommon. While your income is therefore unreliable, this can be a good option if you’ve built a platform of readers eager to pay for your work and/or the other authors in the anthology have a strong platform to market to as well.

Token rates are generally in the $5-$40 range, where the market can’t afford more but feels it’s important to pay something. The Science Fiction Fantasy Writers of America (sfwa.org) has set pro rates at $0.08/word, but you’ll see anything from half a cent on up. Some markets also offer lump sum payments in the 100+ range. Generally, the more they pay, the more the competition, but don’t self-reject—the worst they can do is say no!

Gut Check Break!

I’ll keep repeating this, but ALWAYS read the submission guidelines and follow them. Your story should be creative; your formatting and document presentation should not be. If no specifics are given, follow Shunn Manuscript Format, modern edition as the default.

Some competitions charge entrance fees. Some writing markets charge reading fees, but far from all. You can spend a lot of money trying to get published, but you don’t have to. Avoid fee-charging markets or competitions unless you think your story has an excellent chance of earning the expense back or unless money is no object.

It’s easy to get caught up in the pursuit. After a few submissions, you just really really want an acceptance. Try to clarify your goals and keep them front and center. Write them down and post them in your workspace if that helps.

On a related note, always read the contract. Some market post a sample one. Most competitions will also post terms. Some “opportunities” aren’t. See other posts in the Resources section for links to reading, understanding and negotiating contracts.

Consider the reader(s) before submitting. What kind of reader is likely to appreciate your story (if it’s already written). What might the judges or first readers/editor care about and appreciate? You can research past award-winners or other stories in a magazine to get an idea, but if you’re submitting a lot, it’s not practical to do too much research.

Finally, make yourself a tracking document or spreadsheet early on. Keep track of submissions, contract terms for licensed stories, and details of the stories themselves. This seems silly at first, but if you keep writing and submitting, you’ll quickly get beyond the point where you can keep track in your head.

Indie Publishing

09 Jul 2021

Recommended Resources

Disclaimer: many free resources are provided in hopes that you’ll invest in a product (workshop, book, mentorship program, etc.) Don’t invest in anything until you understand it well enough to know if you’re getting a good deal.

Indie Publishing

If your research tells you the traditional publishing route isn’t for you, you need to actually write a book before you can get it out there on your own. The good news is that technology has made pretty much everything you need more accessible than ever before. The bad news is that you’ve got a huge learning curve ahead. You need to figure out how to write a good book, make it book shaped, get it out to the world, and then keep people interested in it. You may (probably will) need a budget for production costs like cover design, too, if you’re not committed to a completely DIY approach. It’s a journey, it’ll take time, and you’ll make mistakes. But it’s also a strong option in the current market and a way to get your words out to the world and establish a career for yourself.

Indie Publishing Retailers/Distributors

Just a shortlist of options. The top 5 are Amazon, Kobo, Barnes & Noble, Apple, and Google. Distributors can help you get your book out to even more markets and make it easier to get started and coordinate (you set up a book once instead of 5+ times on different sites) but offer less control and flexibility. Most take a portion of royalties in payment (no upfront cost).

Creating eBook Files

The main thing is to get your text set up properly using built-in styles (heading, body text) and page breaks. You can use free software or online setup wizards like Draft2Digital’s. The DIY approach is better for creating small file sizes (important if the retailer applies fees by size) but can be tedious.

Creating Print-Ready Files

Starting from the same file you compile an ebook from, you can update the built-in styles to change font, size, etc., set document settings to match the desired dimensions (most books are not 8.5x11”!) and add layout or visual elements. Professional books have a number of distinctive features: alternating margins (wider on the side the page is bound), kerning (spaces between letters, also spacing between words and lines) to ensure smoothly readible text, widow/orphan control to make sure the text isn’t split awkwardly across lines or pages.

Microsoft Word works just fine for this, as long as you don’t have complex visual layout like a photo book or text layout. Professional designers may use Adobe InDesign. I haven’t tested Google Documents, but it’d probably work fine as well. You’ll need to export to PDF for the printer.

Creating Print-Ready Covers

Cover design is a balancing act between fitting in and standing out. You want to send the message that your book is like other books the reader likes, while standing out just enough that they pick yours up out of the crowd. You can learn cover design, but it’s another whole learning curve, and a poor cover may hurt your book’s chances.

Derek Murphy shares some cover design resources here. Canva is a good free resource for very simple designs and may work well for certain genres.

Publishing Metadata

The last piece in compiling a book is the metadata. This stuff can have a big impact on how well your book reaches readers, and each element should be considered (and tested) to get the best result.

Traditional Publishing

08 Jul 2021

Recommended Resources

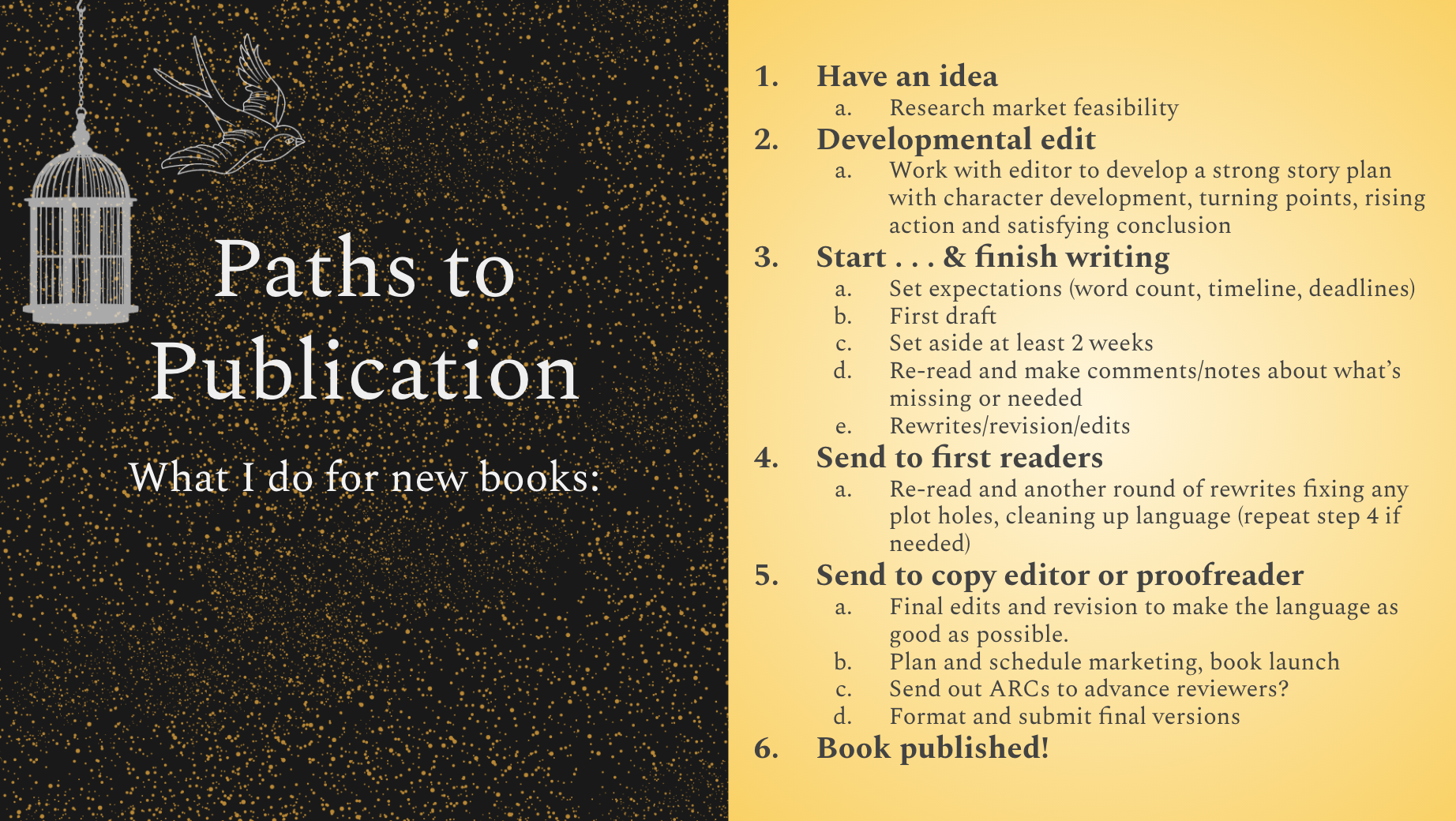

Paths to Publication

Determined to get a book-shaped story out into the world? Here’s a rough outline of what it might look like.

As we’ll look at, traditional publishing is often slower with lots of waiting between steps, and possibly more drafts and rewrites. Agents are not essential but we all act like they are, and it’s unlikely that you can get a manuscript in front of a major publisher without one.

If you choose to independently pubish (self-publish), you don’t have to do every one of these steps, but you do need to either learn to do or learn enough to hire someone to do most of them. And in both cases, your job does not end when that book hits store shelves.

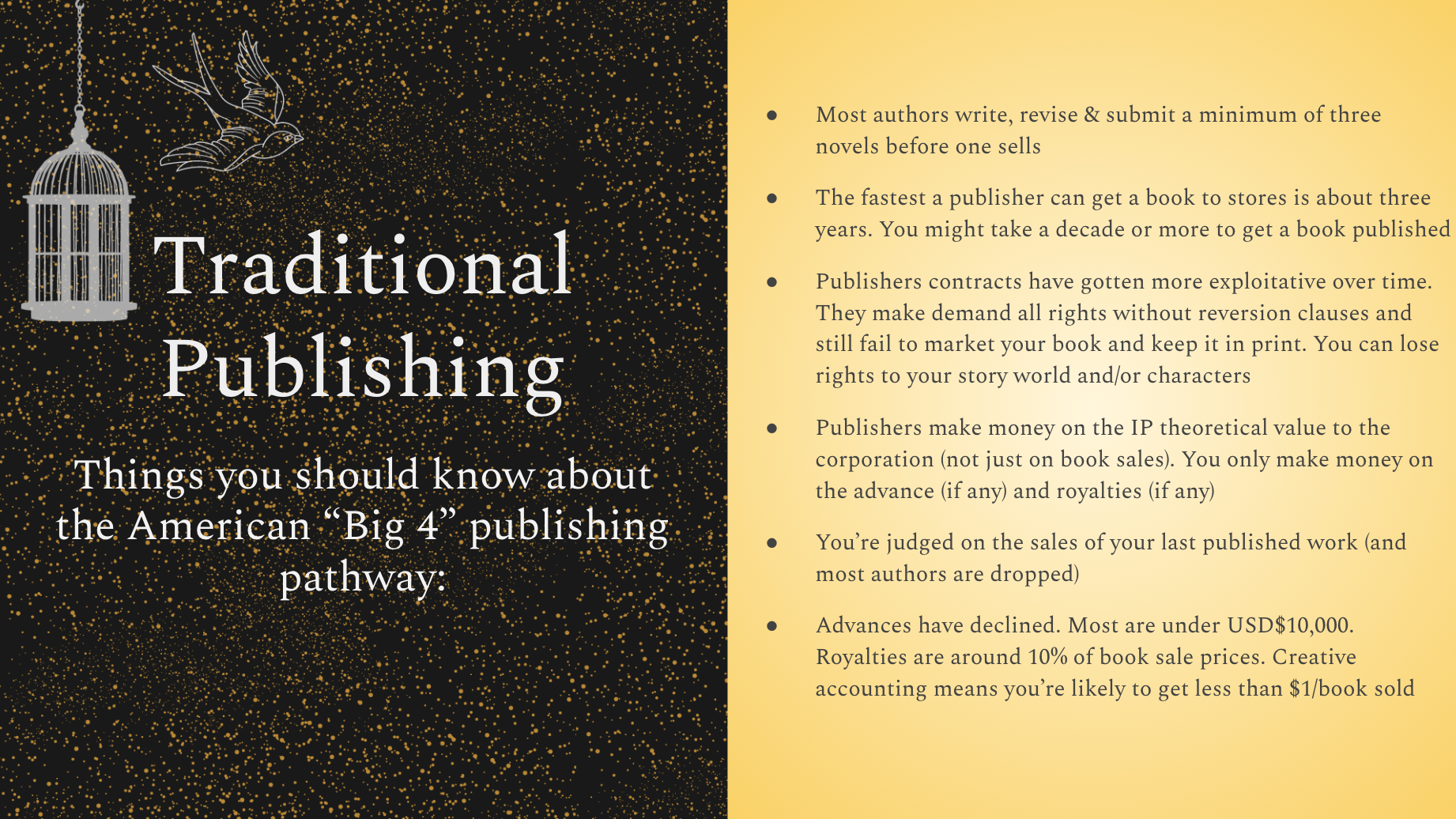

Big 4 Publishing

Most of this boils down to: it’s slow, there are no guarantees, and you’ve got to look out for yourself. The traditional publishing landscape has been getting worse for authors over the years, but do your research and make the best choice for you and your book. Things may change.

Publishing Tips

Agents (and publishers) have been known to steal from authors. That said, there are some very well intentioned people out there. As always, do your research and be intentional in your choices. Small and micro presses often offer better contract terms. They may still steal from you or go out of business. Proceed with caution, and watch out for “hybrid” publishers.

In traditional publishing, all money (should) flow to the author. If you’re paying for anything, something’s wrong. Don’t pay “reading fees” to agents or publishers, that’s a scam. If you have to pay to get the book out there, that’s independent publishing with a services company (“hybrid publisher”), not a real publisher. If that’s something you want, just be careful with the contracts and don’t sign away licenses without getting compensated.

Benefits of Traditional Publishing

Despite the evidence, it’s not all downsides! Book advances have gone down, but you at least get something, rather then spending your money to get published. There is still some prestige to “being published,” particularly by a major publisher. It can open doors. You’ll be eligible for more awards and speaking opportunities (whether you have a chance or want them is a separate question.) If you write for children (babies through to teens, in the publishing world), traditional publishers may be able to get your book out more widely—to public libraries and schools, for instance.

Groups Worth Joining

01 Jul 2021

Facebook turns out to be an unexpectedly essential hotspot of groups for writers. Here are some worth your time:

You’ll also find groups for every interest, purpose, or subset thereof (age range, genre, marketing topic, etc.)

Advice for Teen Writers

12 Jun 2021

Occasionally teens get assigned to interview an author as part of an English assignment or as part of a unit on future career prospects. Answers collected here for easy access:

June 2020:

1. What sort of postsecondary education (if any) or experience did you have and how did it help you become an author?

I knew I wanted to be an author from about the eighth grade on, but everyone in my life insisted I needed a day job because I wouldn’t make any money. So I figured because I loved books, why not become an editor? (Not realizing that other careers in publishing are just as hard to get into and underpaid, lol.)

I was nearly finished with a Bachelor’s degree in English Language (grammar, history, linguistics—as opposed to Eng. Lit., which is more Shakespeare and novel studies) at UBC before I realized it would do absolutely nothing for my prospects as an editor OR as an author. In my opinion/experience, the major didn’t do a thing for me, but some of the things I did in random side classes were helpful (coding websites, using design software.) These days it’s hard to get by without any post-sec education, but in hindsight, I could easily have just gone to UFV and done any arts degree with the same results.

I also took a couple of term-length workshops through UBC extended studies focused on children’s publishing and editing and rewriting fiction in an attempt to snag an internship with Vancouver-based small press Tradewinds Books. Those actually were somewhat useful. It’s important to study your industry and take opportunities for focused continuing ed where you can get them. However, I got buried under finishing my degree and establishing a “day job” for several years, and by the time I was actually ready to publish, my intel was way out of date.

I worked part-time throughout university and was already established in marketing/communications for the Vancouver engineering industry by the time I had graduated, and worked for several years in that before finally returning to publishing. That ended up being fairly useful in terms of relevant experience (and launch funds). Understanding business, the basics of marketing, communications, social media, how to read a contract, etc. all give you an edge.

My recommendation to young writers is to get a two or four-year degree in something they’re interested in and might find useful. Business is a fantastic choice because if you become an author, you will be a small business owner. Marketing/communications are useful. Comp-sci or anything tech-related can come in handy.

You don’t need a creative writing or English degree, but if you’re set on it, there are worse things to do with your time. And you’ll need to have a plan for earning money, at least at the beginning. Few jobs are 100% secure these days, but jobs in the Arts are less reliable than most. There are authors out there making steady incomes (or, in some cases, exceptionally good incomes) but it’s usually something you have to build up to over the course of years. (Royalties can start to add up as you get more books out, as long as you don’t license to a publisher that lets it go out of print.)

2. What does a day in the life of an author look like? How often do you write?

I don’t subscribe to the “must write every day” camp of authors, so my schedule varies depending on the current project. I also work best when I don’t have to multi-task and switch gears that often, so I try to set aside time in batches to work on writing, instead of putting in an hour a day or whatever.

I teach weekly creative writing workshops during the school year (and camps, in the summer). If I’m in the middle of one or preparing for the next camp, I’ll spend time writing feedback, providing copyedits, preparing presentations, or developing curriculum. On a standard week during the school year, that’s 1-2 days on marking and prep, plus a half-day on the actual workshop.

I also freelance as a business marketing and communications consultant, though I try not to let it eat up too much of my time. So I may lose a few hours a week to writing or rewriting corporate content or sorting out a client’s tech woes.

I’m on the board of the Children’s Writers and Illustrators of BC Society, (currently Treasurer, nominated as President come July) so that’s another hour or two a week responding to requests. (But membership societies are worth the effort from a career opportunity perspective—definitely join one when you get the chance!)

Then there are the not-writing parts of being an author. I send a newsletter every second week, spend a couple hours on social media a week, several hours on things like emails, paperwork, accounts, and research, and a few hours on advertising. I do a lot of things myself, from creating graphics to bookkeeping to coding my website, so it all takes time. Submissions and queries (when I’m working with a publisher) also sit in this huge general “administration” pool. All sorts of random occasional stuff like book formatting, updating book listings, sharing review copies, etc. also fits here.

As much of all that as possible gets pushed to the side for actual book production. You get faster as you go, so at this point, I’m spending about a month on planning/prep/research for any novel-length works, about a month on the first rough draft, another two weeks each on a markup and a rewrite pass, and then another week each (or less) for revisions/rewrites/final review. I’ll spend maybe four to six hours a day when I’m in book mode. (The rest of the time is for unavoidable chores from the previous lists.) And there are two weeks to a month’s break between each step to catch up on everything I ignored while I was writing.

For short fiction, I kind of just throw those together whenever a rare slow day crops up.

So to sum it all up, I work from home and on my own a lot, which suits me. And I’m on the computer from maybe 8:30/9 in the morning to 7-9pm (with breaks to make meals) weekdays and maybe 6-8 hours/day on weekends. Depressingly, most of that time is spent on things other than the actual writing, lol. Again, writers are small business owners, so our experience is not that different from entrepreneurs!

3. How do you get inspiration for a book?

This sounds a little (or a lot) loopy, but dreams are a big influence, actually. If I have a really entertaining lucid dream, I’ll often make some notes and come back to it. I also think about and do research on industry trends and the current market to try to pick something that may connect with readers. Other books, tv/movies, etc. often provide inspiration I’m unaware of until I look back and see the influence. Same thing with real life—in hindsight, I realized I’d used a lot of places and experiences for “fantasy” settings and situations, just with a twist. In general, I have no problem coming up with ideas, so it’s more a matter of weeding through all the options to find something I’m interested enough in and that has a strong chance of connecting with readers.

4. What is the process of publishing your books? Was it very difficult to get it published and how do you advertise your books?

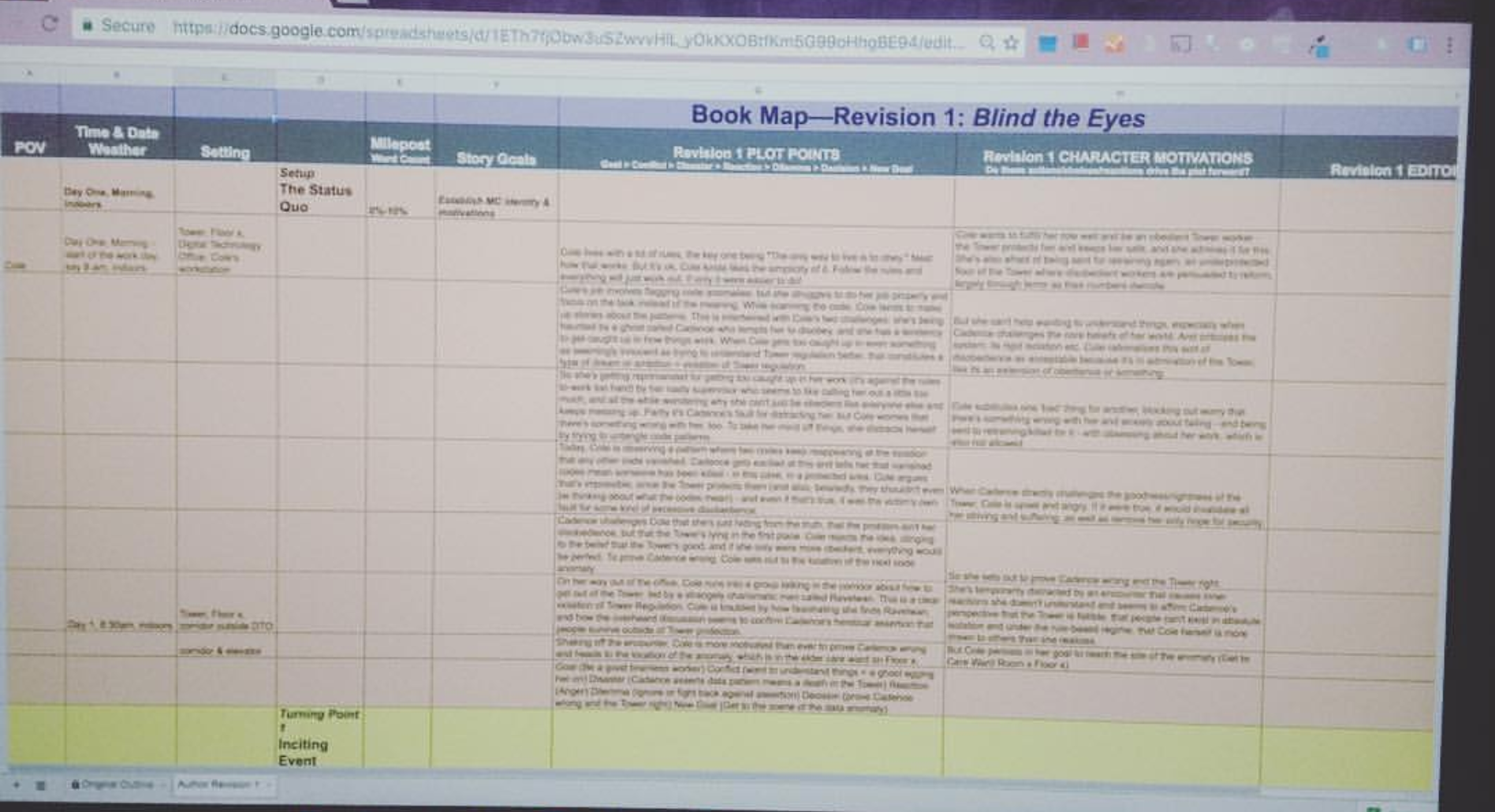

With my first book (Blind the Eyes), I was operating on out-of-date information and was aiming for a “Big 5” traditional publishing deal. (In the 2000s, YA books were selling in seven-figure deals, dystopian and paranormal subgenres were hot, and contracts hadn’t gone quite so sideways.) So I spent a couple years writing and then hired a developmental editor to help me get it in the best possible shape for publication. (Learned a lot about story structure and character development!) Then I started querying literary agents.

But by the time I started receiving “full requests” back (a positive result, signalling agent interest), I had started researching the current publishing industry and realizing that (a) I didn’t want to sign over my rights and was very done letting big businesses run my life (b) I might have the skills and resources to build my own career. I figured if agents thought my book would be worth money to them and to publishers, that was a promising sign that it could have value to me even without them.

So I hired a proofreader (it had already gone through a couple rounds of editing) and a cover designer, set up a bunch of promotions, and launched it independently. From a technical standpoint, there’s definitely a learning curve to this approach but it’s not all that difficult. And the way I did it, there’s also some cost, although the more skills you develop yourself, the lower that cost can be.

The last two books have followed the process I outlined below question 2: prep work with my developmental editor, rough draft, couple weeks to a month rest time to get some perspective, read through and markup notes for revisions, wait 1-2 weeks, actual rewrites, send to first readers, third revisions, send to proofreader, final clean-up edits, format, send ARCs, upload final ebook and print editions to storefronts. I have a rough timeline in mind, but I start setting hard dates and ramping up marketing around that third revision or when I send to proofreader.

And then short fiction is kind of its own thing. Contracts are much more favourable, so I do sell short fiction to traditional markets. I do a quick draft, often in one sitting, re-read and clean up, and then start submitting to magazines or anthology calls. Most of the time on short fic is spent on submissions (and endlessly waiting on responses—it can take months).

Advertising and marketing is a huge topic in and of itself, but in a nutshell there are ongoing/longterm efforts and then launch or special promo pushes. In general, I try to make sure my brand is strong and my books are visible as many places as possible. That means a website and listings on every industry site I can manage. Social media. Newsletter “swaps” with other authors. I build connections and maintain them through social and a regular newsletter. I do paid advertising on an ongoing basis (mostly Amazon ads) but in all honesty, I haven’t really cracked the code to sustainability on that front.

For new book launches or special sales, I schedule paid promotions through book deal newsletter services, maybe a small blog tour, sometimes a few days of Facebook ads, and then keep the Amazon ads running. It’s important to keep in mind that some books fit the market better than others and offer better return on investment. My books seem to do well with ongoing/traditional marketing efforts but not as great with paid advertising.

5. Is there anything you wish you would have known before you wrote/published your first book?

Haha, so much. I’ve mentioned it a few times, but I thought I understood a lot about the industry when I was writing and moving toward publishing my first book. My information was out of date. This industry moves fast. Subgenres, tropes, markets, contract terms, formats, everything is in flux. So some decisions I made around the kind of book I thought I should create and what I could hope for in terms of a career were pretty off base.

I also wasn’t as comfortable with story structure and planning out novel-length (or series-length) stories as I could have/should have been. It made for a lot heavier rewrites on book one!

And I was hyper-sensitive about quality because I’d come from a corporate career and didn’t want indie publishing a sub-par book to reflect badly on me as a professional. In hindsight, I procrastinated, angsted, and focused too much on presentation when I should have been focusing on telling great stories and getting them out to readers.

That said, writing (and publishing) is also a very learn-by-doing skill. You try things, you learn, you adjust.

Post Index

Publishing Overview | 11 Jul 2021

Short Fiction Overview | 10 Jul 2021

Indie Publishing | 09 Jul 2021

Traditional Publishing | 08 Jul 2021

Groups Worth Joining | 01 Jul 2021

Advice for Teen Writers | 12 Jun 2021