Recommended Resources

- The blog archives and weekly business-for-writers blog by Kristine Kathryn Rusch is gold. This section is particularly essential: Contracts & Dealbreakers

- The Plot Whisperer: Secrets of Story Structure Any Writer Can Master by Martha Alderson (gets a little new-age-y but generally provides a good foundation)

- Developmental Editor Lisa Poisso collects useful resources on her Clarity subsite

- Reedsy offers plenty of free articles, guides and mini courses on their blog

- The Creative Penn offers a wide variety of learning resources (delivered authoritatively, but take with a grain of salt) on this blog

Disclaimer: many free resources are provided in hopes that you’ll invest in a product (workshop, book, mentorship program, etc.) Don’t invest in anything until you understand it well enough to know if you’re getting a good deal.

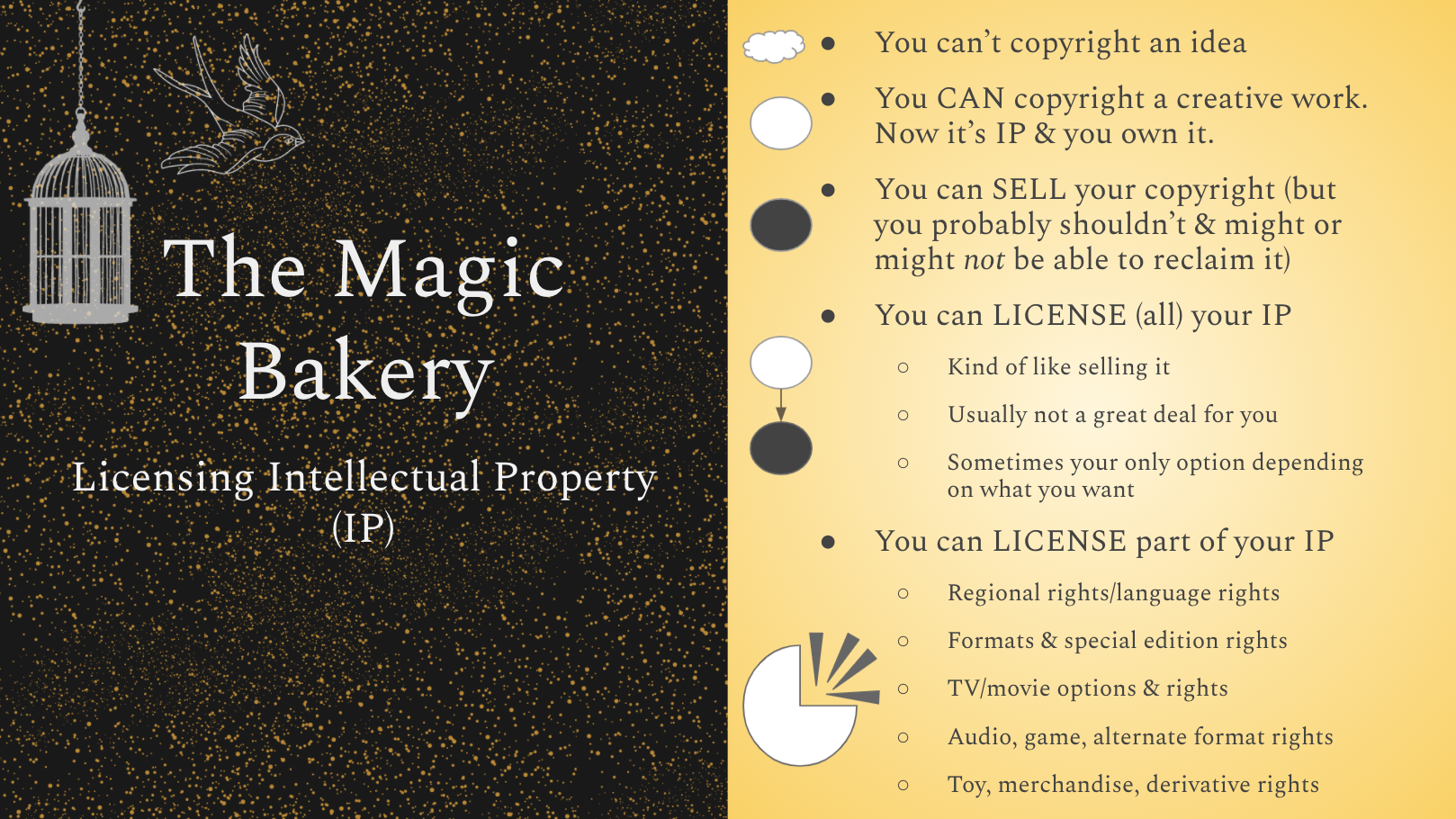

Licensing & YOU

Experienced and prolific author/editor/publisher Dean Wesley Smith talks about the idea of a “magic bakery’ when it comes to writing. You can read about it in his own words and in this excellent blog by his wife, Kristine Kathryn Rusch. But, in a nutshell, the concept is that intellectual property—like our writing—can be sold over and over, in part and in whole, unlike other goods.

Your work automatically belongs to you from the time of its creation. You own full copyright. (The exception is when you’re writing as work-for-hire, or working on an IP project that belongs to someone else, like a Star Wars tie-in novel, for example.) Technically, you could transfer copyright in a sale (if you sign a terrible contract), but don’t.

Instead, you license the right to use the work in part or in whole. Some examples: Licensing first publication rights in English, then, when the exclusivity period expires, licensing reprint rights (over and over again) or publishing it yourself as a standalone or in a collection. You can also license (and re-license) translation rights, audio rights, production rights (for film/tv), merchandising rights, etc. All that off of one story (potentially).

The moral of the story? Keep your copyright, don’t license more rights than the licensee will use (to your benefit), and make sure your contracts aren’t perpetual (so you can get licensed rights back eventually and re-license them.)

Publishing Novels

They’re a bigger effort in terms of time, skill, and investment, but novels are not inherently better than any other type of fiction. Try not to feel pressured into writing one if you don’t really want to!

Whatever publishing path you choose, you will become a small business. Like any entrepreneur, you’ll need to learn business skills and keep up on your industry, even if it’s just a side hustle. Do your research as you approach publishing; things change in a matter of months in this industry, much less years, and you don’t want to be launching with outdated intel. See other posts in the Resources section for links to groups and news outlets for staying up to date.

Publishing can pay, but it’s usually a slow and gradual path to earning an income. Royalties can accumulate over time. The opportunity to sell additional licenses may emerge. The more stories/books you have out, the more it all can add up, but that takes time, too. Make a plan for how you’ll survive financially for the first years at least.

Be open to nontraditional routes: serial fiction and subsidized or serialed fiction are looking strong right now. Patreon and Kickstarter are good examples of emerging trends that authors have leveraged to the advantage of their careers.

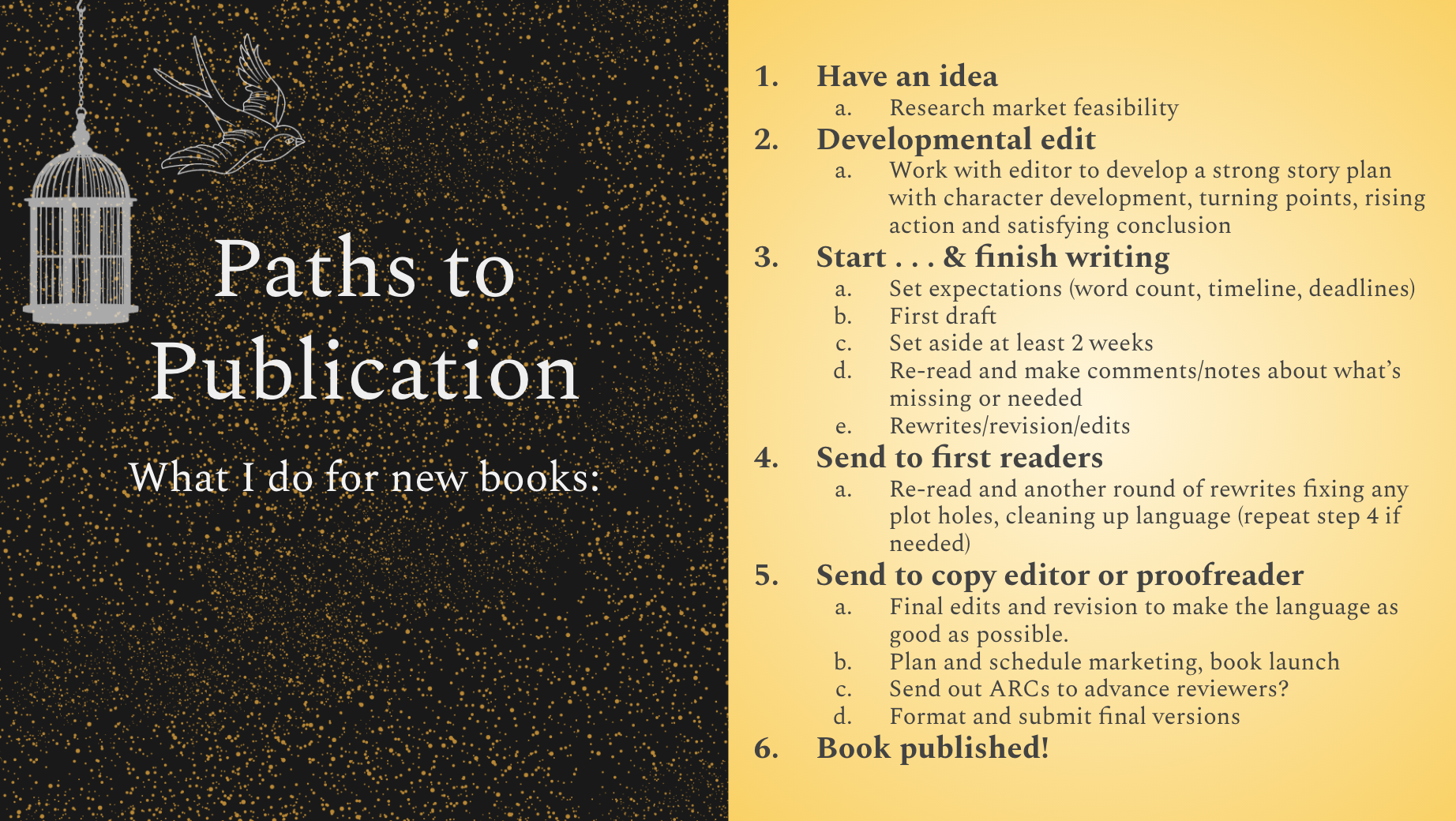

One Route

Not much to add here. This is roughly what I do these days. It’s pretty minimal compared to some, unneccessarily complex compared to others. I can’t quite bring myself to draft-proofread-publish, but I’m not doing multiple rounds of heavy rewrites, either. If I get really stuck on the plotting, I’ll change formats, which can look like any of these:

|

|

|

|

|

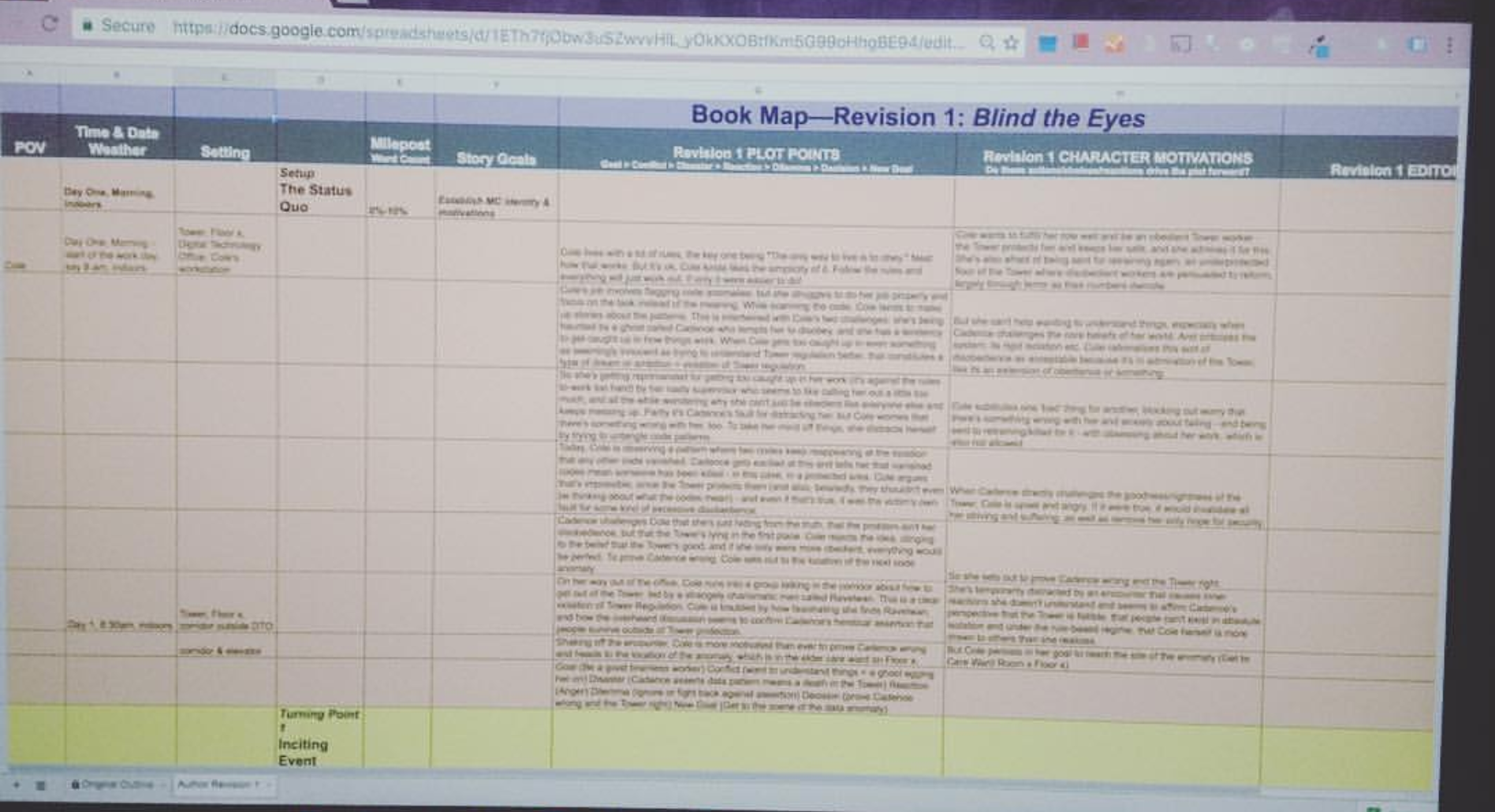

Story Mapping

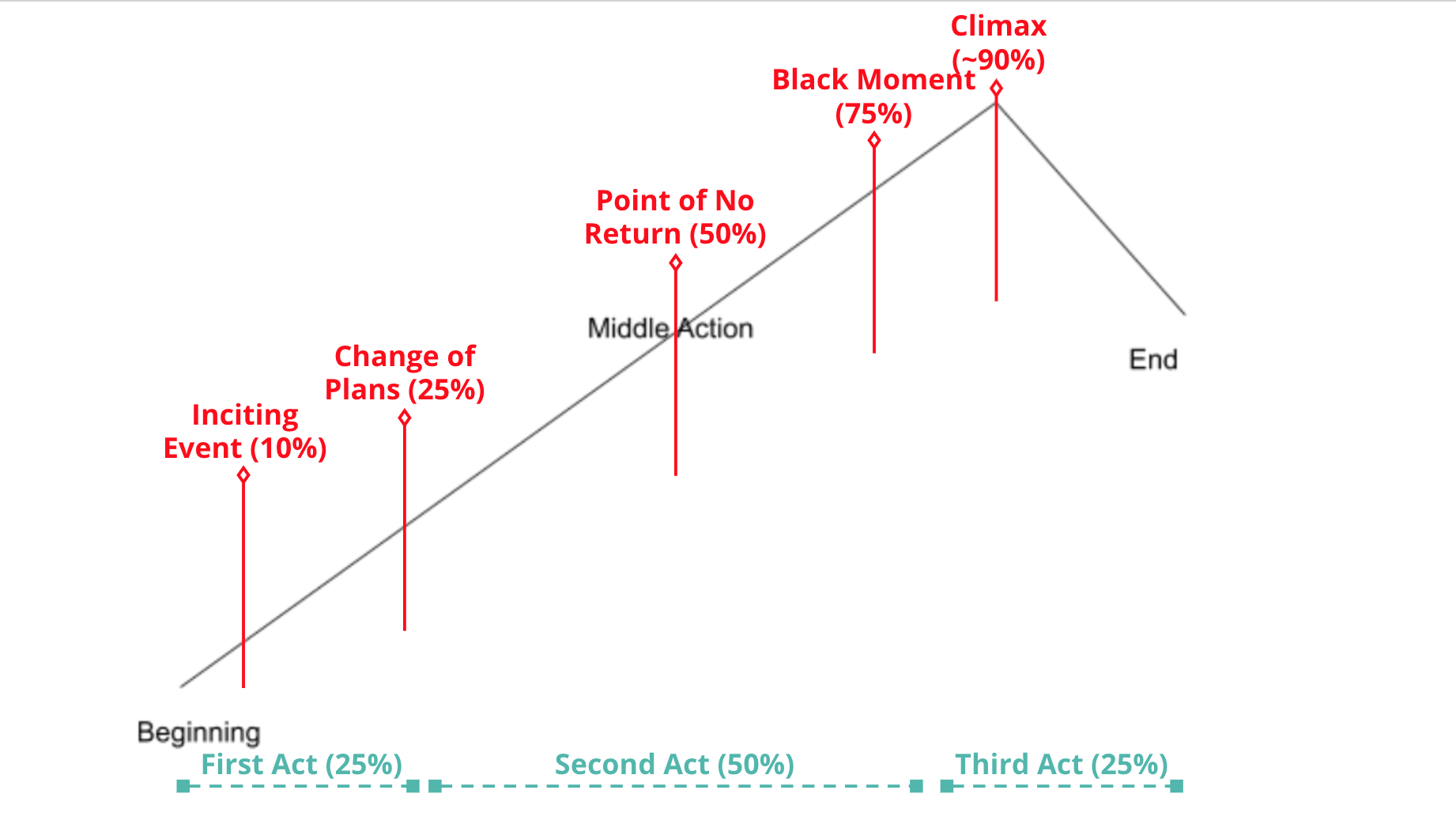

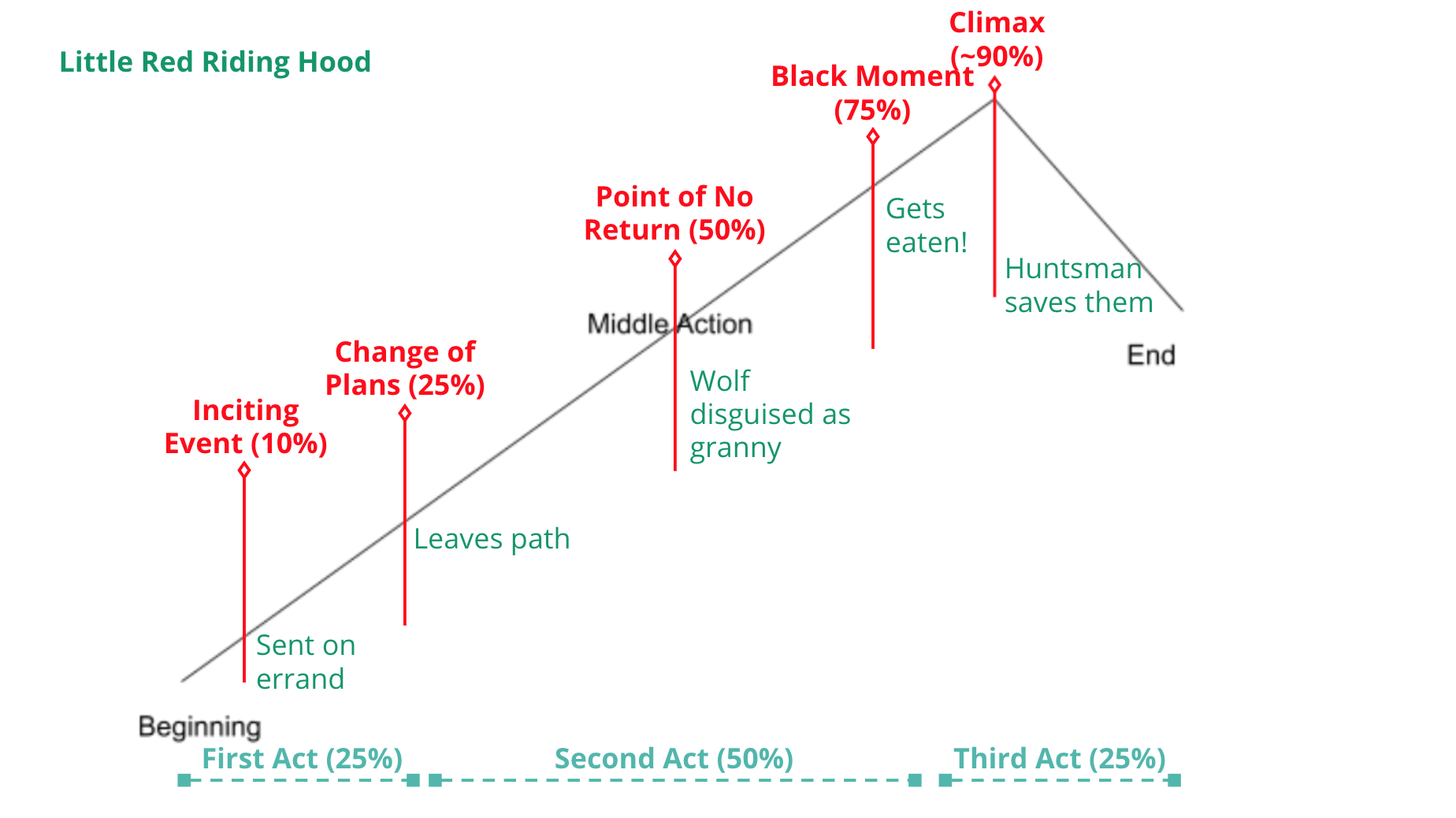

While all the charts and cards can look complex, the basic structure I’m using is a three act structure with four quarters.

The first quarter and the first act map together and contain the inciting event early on (at about the 10% mark). Something disrupts the main character’s ordinary life and sends them in a new direction. It ends around the 25% mark with the change of plans turning point. This is where the main character chooses (or gets dragged into) the adventure/quest/journey of the story.

The second act is easiest to understand if you split it evenly in two. The first half is the character struggling to make forward progress and understand their situation/world/challenge/self etc. Around the 50% mark or midpoint turning point (end of the second quarter) they make a discovery or realization that shifts their trajectory.

Now, starting the third quarter, the main character(s) (thinks they) know what they need to do to succeed, though they still face obstacles. The second act/third quarter ends with the black moment turning point, the darkest point of the story, either figuratively or literally involving death. The main character may feel as though they’ve failed, there’s no hope, maybe no point going on. They may be focused on revenge or retribution.

But, into the final quarter/act, they’ll need to rally enough to take on the greatest challenge of the story in the final turning point, the climax. Often this follows a mini arc of setting out, making progress, making a sudden realization that changes their perspective or goal, hitting a “black moment” of despair, and then rallying to overcome (in a positive story arc, at least). There’s often an inner and outer component to this, the main character finding inner strength or understanding in order to overcome the outer challenge of the story. The last 10% or so of the final act wraps up the story by showing the new normal—and/or setting up a sequel.

Little Red Riding Hood isn’t the best example because it’s missing main character agency in most variations. Ideally, you want your main character’s actions and choices to be integral to every turning point.

If you hate how structured this all is, welcome to the club. I fought this idea hard—but it really does result in faster drafting and stories readers seem to enjoy more. And there’s tons of room for creativity within this loose structure. Also, those percentages will come in handy in a moment.

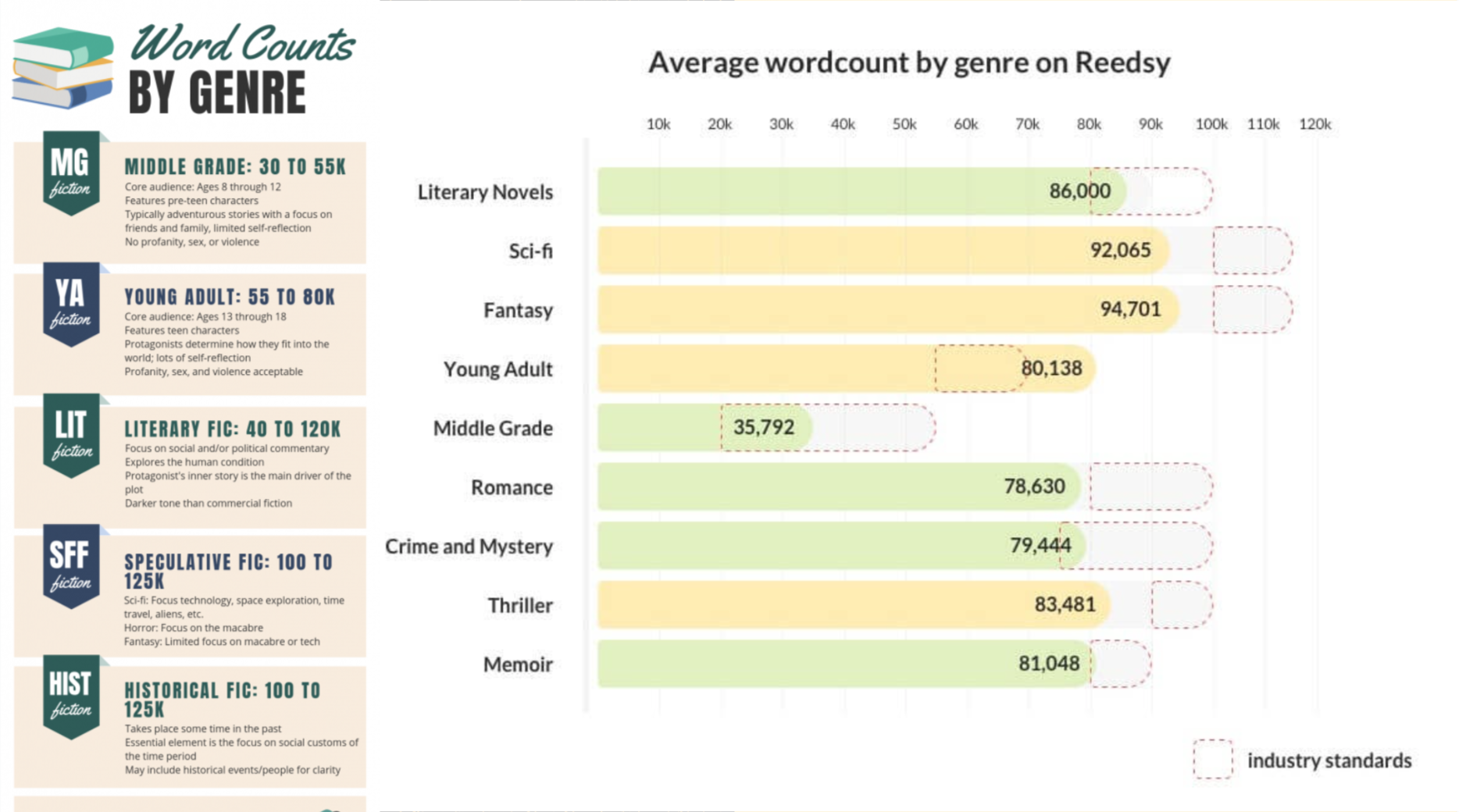

Word count graphics from btleditorial.com & Reedsy.

Word count graphics from btleditorial.com & Reedsy.

|

|

Math For Authors

Everyone’s favourite, right? But hang in there, this comes in really handy.

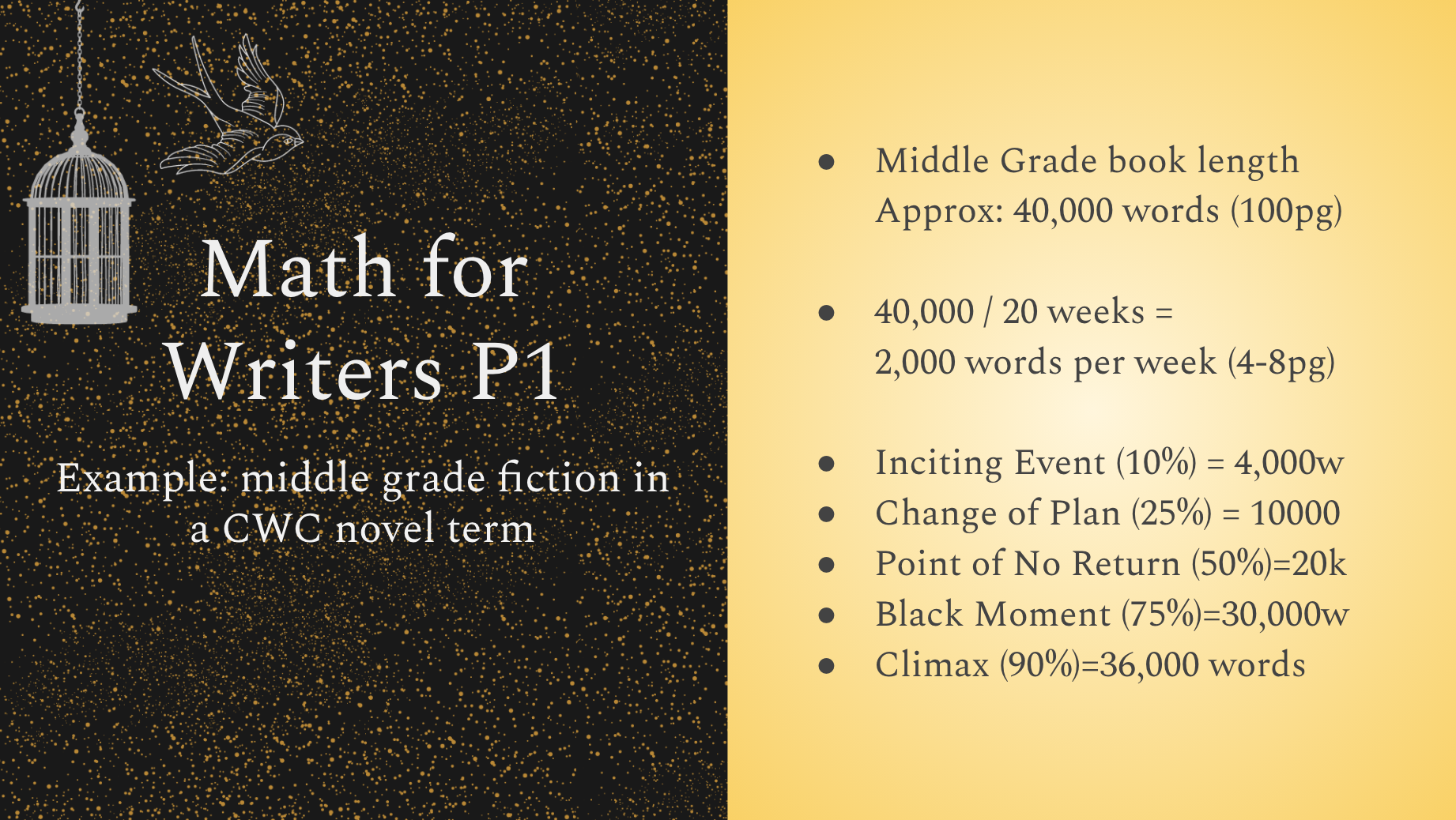

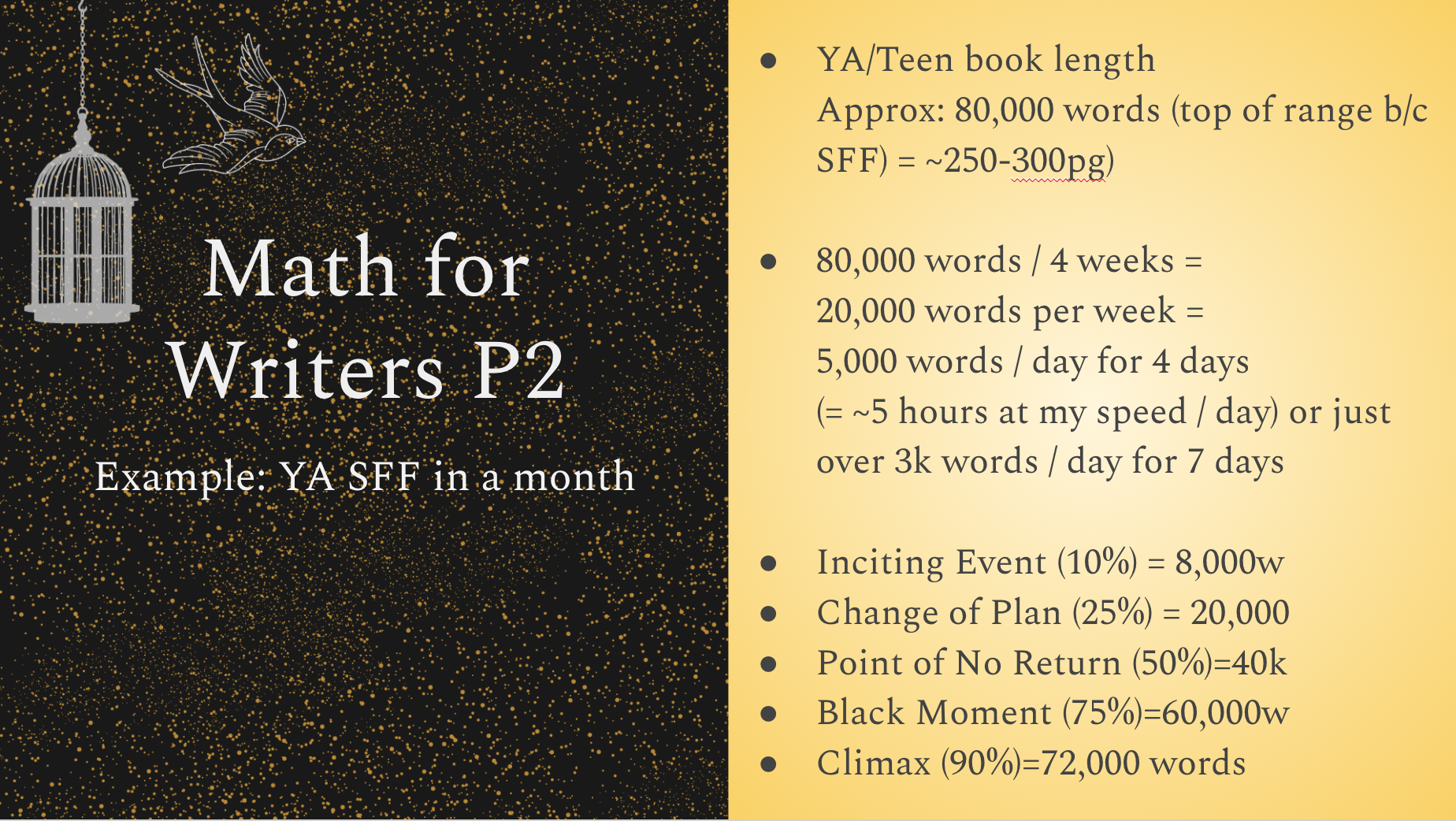

You can apply the turning point percentages we just looked at to a target wordcount (above) to plan how to draft your novel. Pick a target wordcount, jot down some notes about each turning point (or go in blind, if that’s your preference), and track your wordcount as you write.

For instance, if you’re planning an industry-standard middle grade novel (40,000 words, say), as you’re coming up to 15,000 words you know you’ve got the midpoint coming up and you need to get your character in place within the next 5,000 words or 4-5 hours of writing.

If your target is 80k words for a YA fantasy, you’re going to be preparing to write that midpoint as you near 40k words (or try to include an inciting event within the first 8k words, or a black moment around the 60k mark, etc.) These intervals help make stories feel like they’re moving along at a natural clip to western readers who are mostly used to this story pattern. If you’re far off these proportions, it can manifest as portions of the story feeling slow-paced or rushed.

But, as with all writing advice, you can take it or leave it. Other story structures exist. Some writers have stronger instinctual structure, while others find it easier to write to a plan. There’s no one right way, but if you’re not sure where to start, I suggest trying this structure.